We’re closed on Sundays because it’s God’s Day

Appetite is proud to present We are closed on Sundays because it’s God’s day, a group show on the origin, function, and subject matter of mythology. What do we learn from the stories that we have told about strangers, gods, animals, and each other? From the Ramayana to the Odyssey to I Ching to Genesis, myth is the enduring and universal story of the human condition.

In other words: “Mythology is not a lie: mythology is poetry, it is metaphorical. It has been well said that mythology is the penultimate truth — penultimate because the ultimate cannot be put into words. It is beyond words, beyond images, beyond that bounding rim of the Buddhist Wheel of Becoming. Mythology pitches the mind beyond that rim, to what can be known but not told.” (Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth, 1988).

An exercise in comparative mythology across time, culture, and geography, our show features works by Gonkar Gyatso, FX Harsono, Luke Heng, and Ben Loong. God’s Plan is open to the public from February 9, 2021 — May 1, 2021

Ben Loong

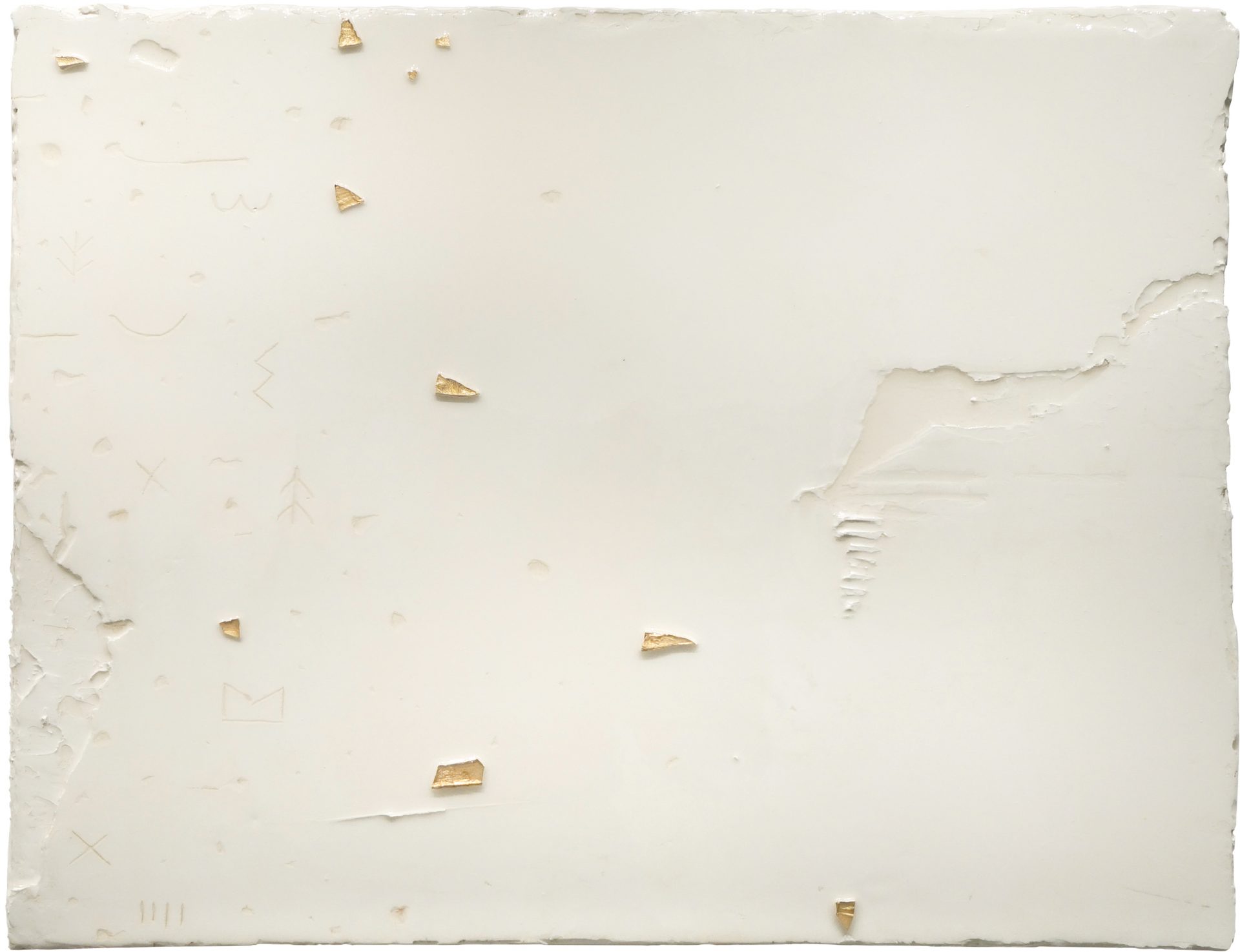

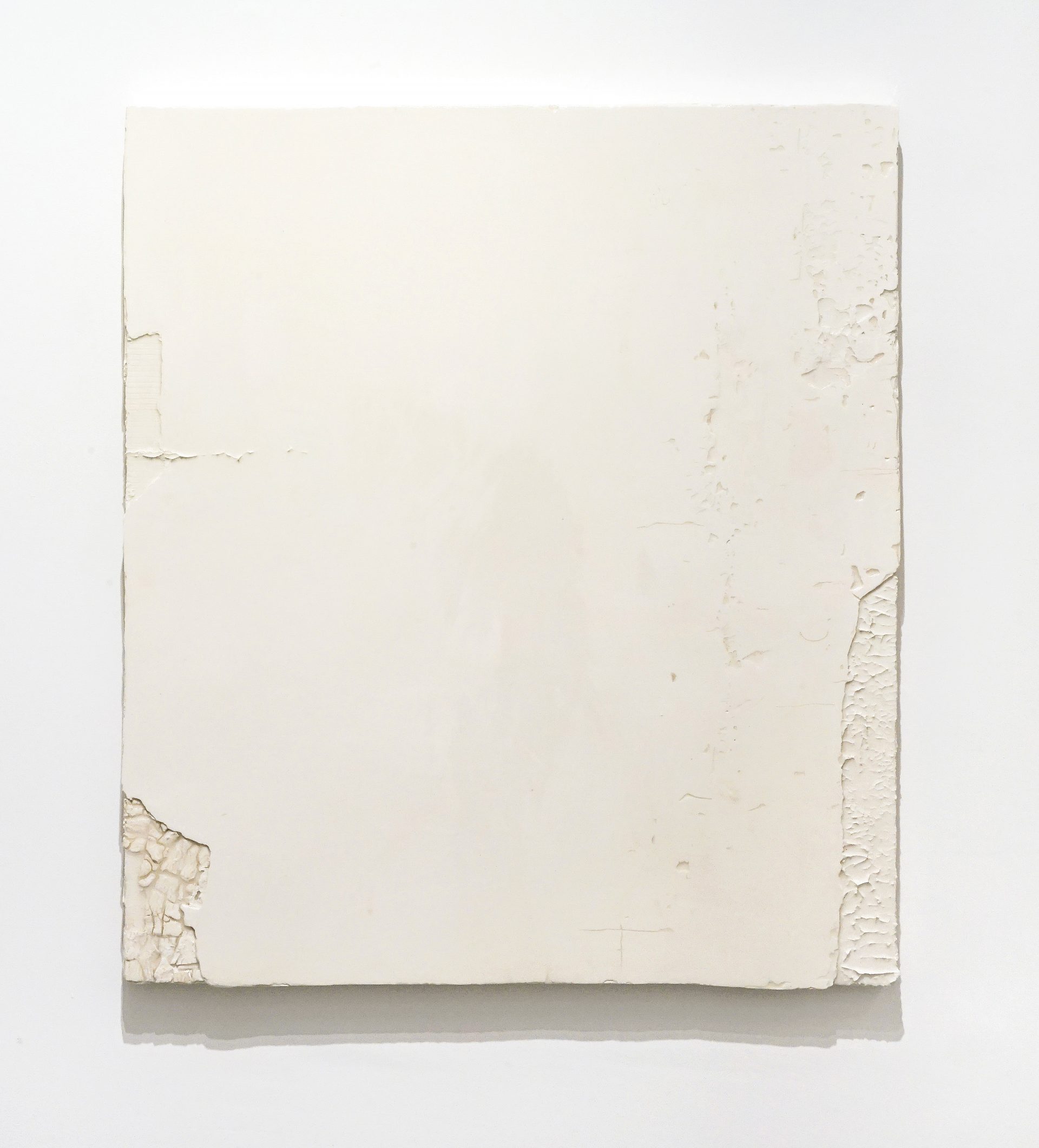

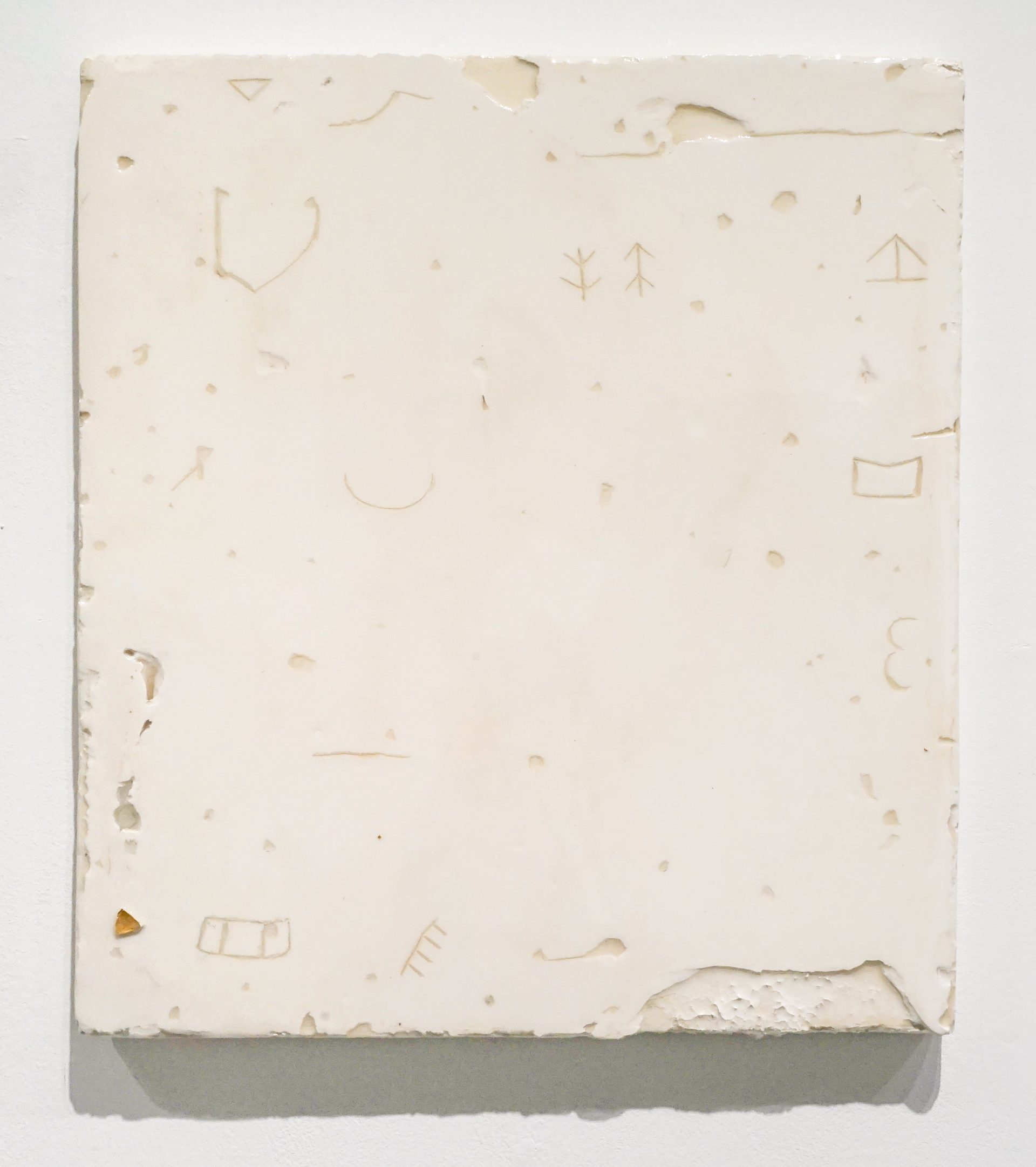

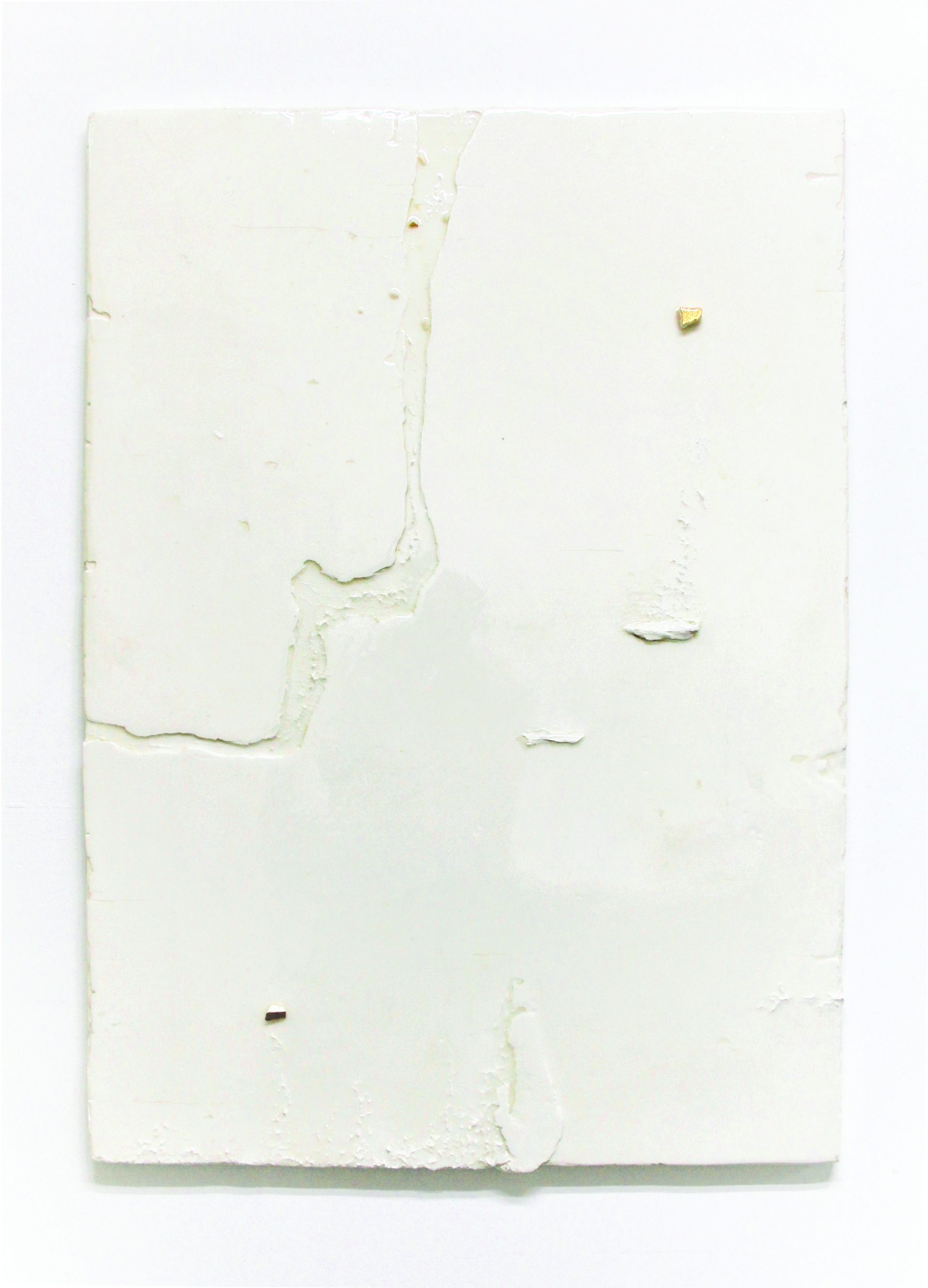

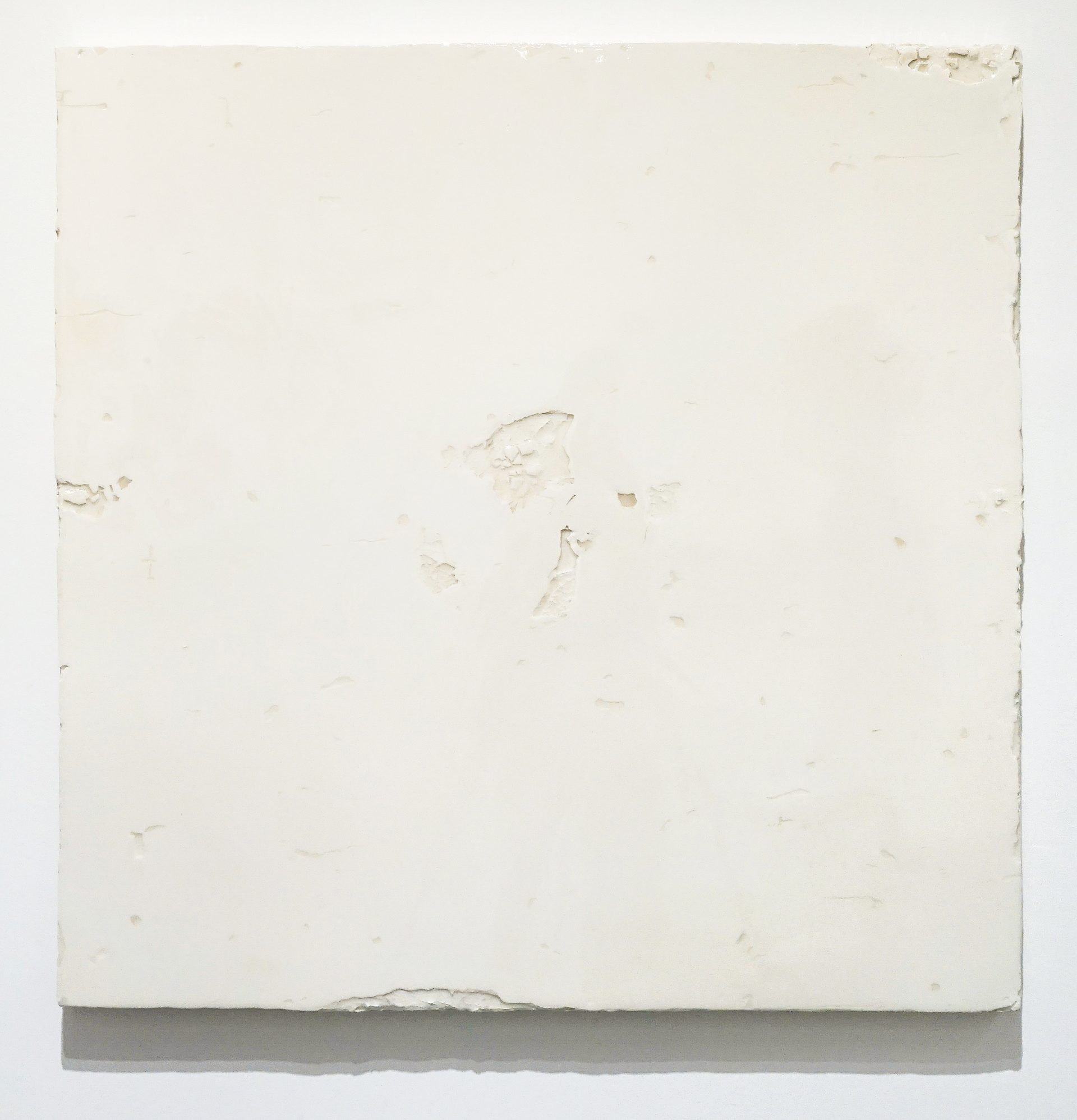

Ben Loong (b. 1988, Singapore) is an emerging Singaporean artist who investigates pathways of human communication and connection. Inspired by phenomena ranging from geologic features, to narrative and spiritual archetypes, to the earliest instances of visual expression, he abstracts these themes into the surfaces of his signature monochromatic drywall plaster pieces. Loong is represented by Mizuma Gallery, and in 2018 was named Highly Commended Established Artist in UOB’s Painting of the Year competition. His recent solo exhibitions include MONO, S.E.A Focus, Gillman Barracks, Singapore (2020) and Aggregate, I_S_L_A_N_D_S, Singapore (2018).

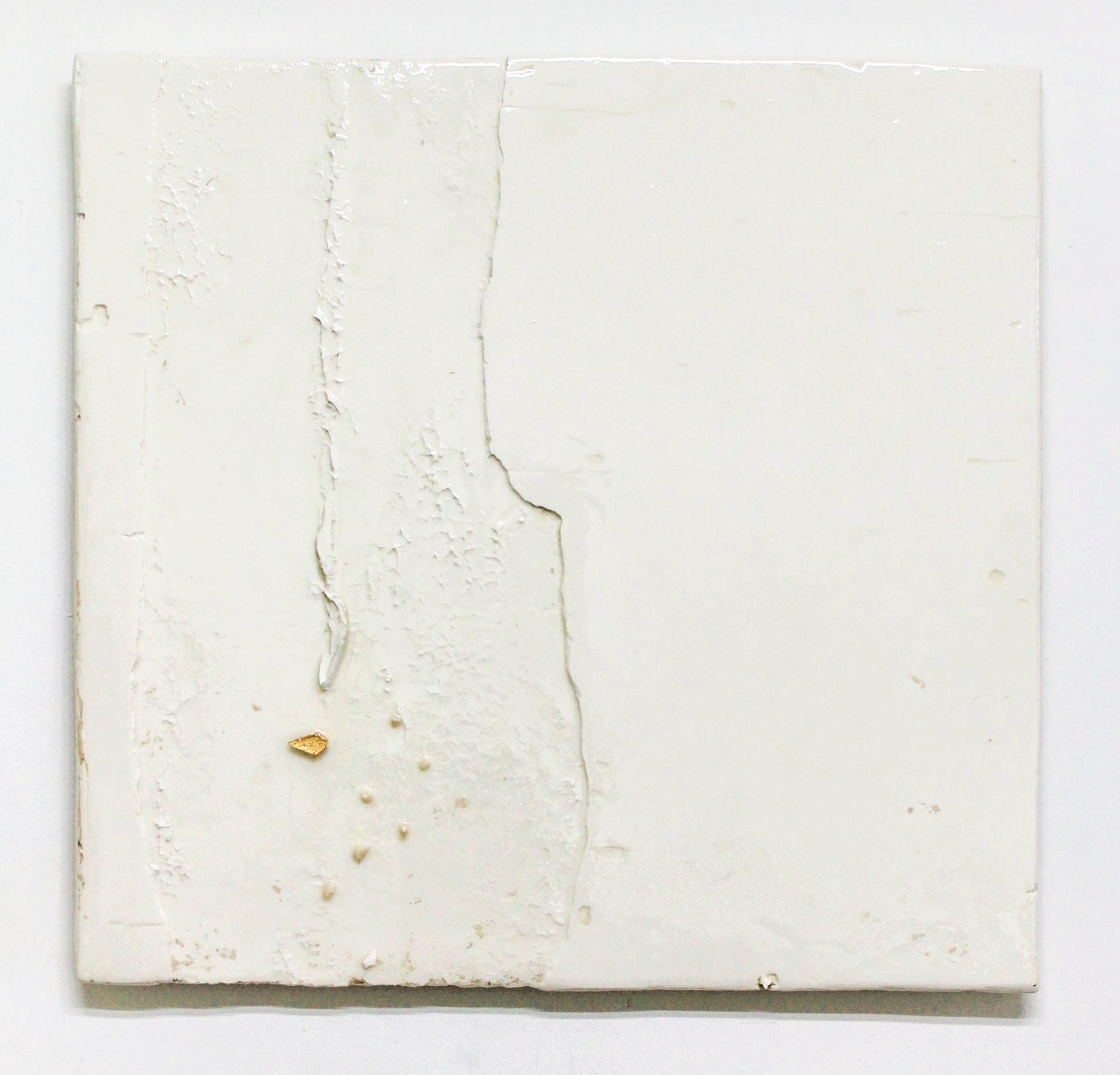

Monolith (2019) is an apt reflection of his practice. A smooth, undisturbed plane occupies nearly the entirety of the work’s surface—an imposing presence framed by two rough edges, reminiscent of a rock relief. Glyph 2 (2019) and Glyph 5 (2020) feature more heterogeneous surfaces, with furrows, craters, and gold leaf-illuminated jags. True to their titles, these pieces are also inscribed with a multitude of glyphs that have origins in the Upper Paleolithic period.

Most commonly found carved into rocks and cave walls, these signs speak to an impulse for visual expression starting from the very beginnings of humanity’s artistic tradition. Archeologically, the purpose and meaning of the symbols are unclear—theories range from emblematic clan signs, symbolic information about an area, or an early form of sign language. Nevertheless, they are indicative of a liminality in our earliest history, where art, language, symbol, and tradition—things that make us human—began to establish themselves. Most remarkably, these symbols have been found in caves and on rocks on every continent inhabited by humans.

For Loong, they serve as inspiration for his own work, and a validation of symbolic thinking and art as intrinsic aspects of human nature. Further, drywall plaster’s contemporary connotations of labor, industry, and craftsmanship form a compelling incongruity in combination with symbols in use millenia before the development of written language. Loong’s careful scoring of these glyphs into the material that the artist is familiar with reenacts simultaneously both primeval and modernized acts of production that would otherwise be isolated by time, and brings ossified, archeological works of art back to life.

Ben Loong

Fragment

2020

Resinated gypsum plaster and gold leaf on wood

44 × 44 × 2.5 cm

Mizuma Gallery

Exploration of fundamental ways of being, creating, and expressing is a unifying theme across his practice. Loong’s MONO series—which includes Monolith (2019)—engages with the patterns common in myths and stories across cultures and through time, such as that of ‘The Hero’s Journey’ or flood myths. The enduring power of these archetypes and their universal presence is their ability to show us that, in Loong’s words, “either everything is made up, or that nothing is made up”. With industrial plaster, he unearths threads of connection through time and space embodied in mythical paradigms and Stone Age symbols, and invites us to be open to discovering common ground in unexpected places.

Gonkar Gyatso

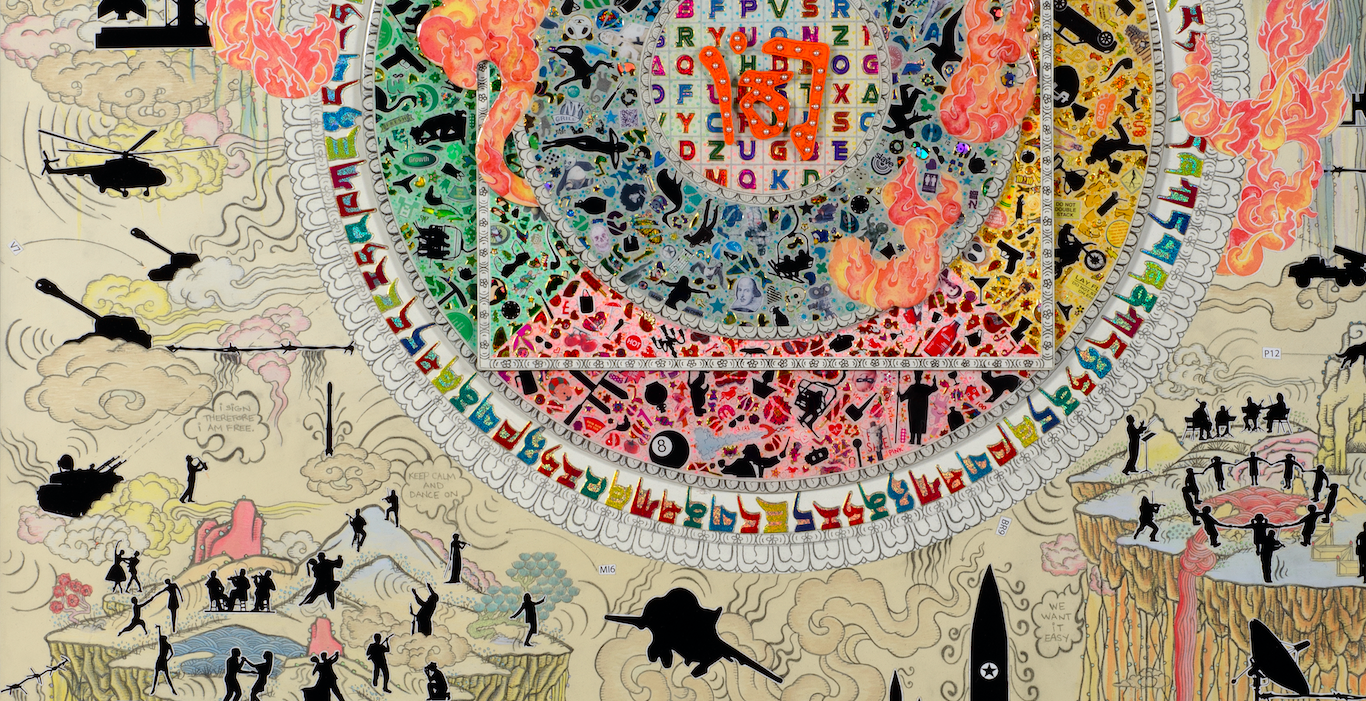

Gonkar Gyatso (b. 1961, Lhasa) is a Tibetan artist who has been based in London since the late 1990s, known for blending elements of Buddhist iconography with Western pop culture in his distinctive wry, lively style. Having grown up in Tibet during China’s Cultural Revolution, studied traditional ink-and-brush painting in Beijing, trained in traditional thangka painting in Dharamsala, India, and obtained an MFA from Central St. Martins College of Art and Design in London, Gyatso epitomizes the transcultural spirit that saturates his practice. His work has been exhibited and collected in prominent institutions worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art (NYC), National Art Gallery (Beijing), Tel Aviv Museum of Art (Israel), and the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston).

His work deals heavily in themes of formation and fusion of identity, exploring self-concept along national, cultural, political, and religious axes. Gyatso articulates the cultural diffusion and hybridization symptomatic of globalization by weaving elements of Western pop culture—brand logos, characters from entertainment media, and municipal symbols, to name a few—into traditional frameworks of Buddhist iconography. After mastering traditional thangka painting in Dharamsala (where Tibet’s government-in-exile is located), the artist developed an affinity for the iconometric grid integral to the composition of these pieces, utilizing the form as an expression of Tibetan identity. By adapting thangka painting (which is heavily symbolic and must be produced according to strict guidelines with origins in Buddhist scripture) as a vehicle for communication, Gyatso merges seemingly contradictory desires for both individual expression and group identification.

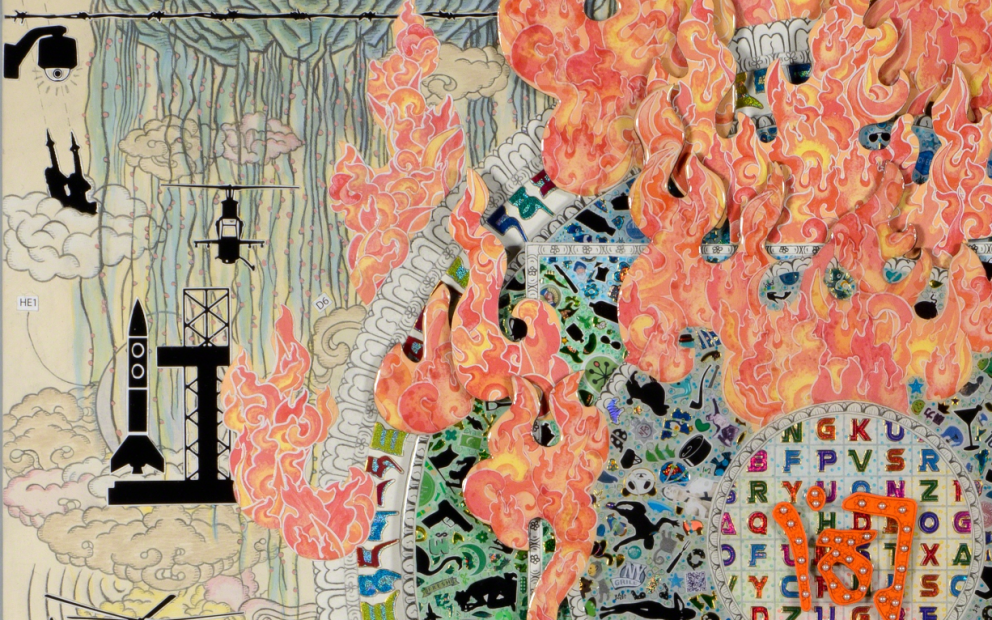

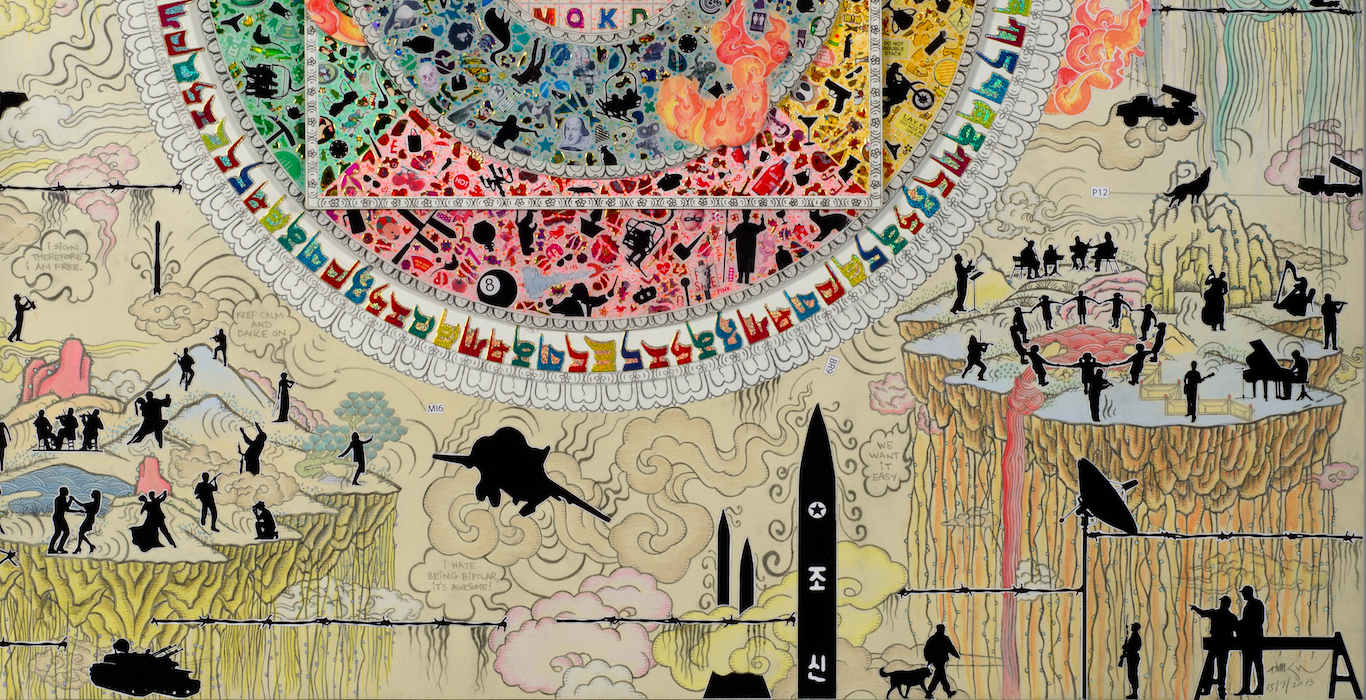

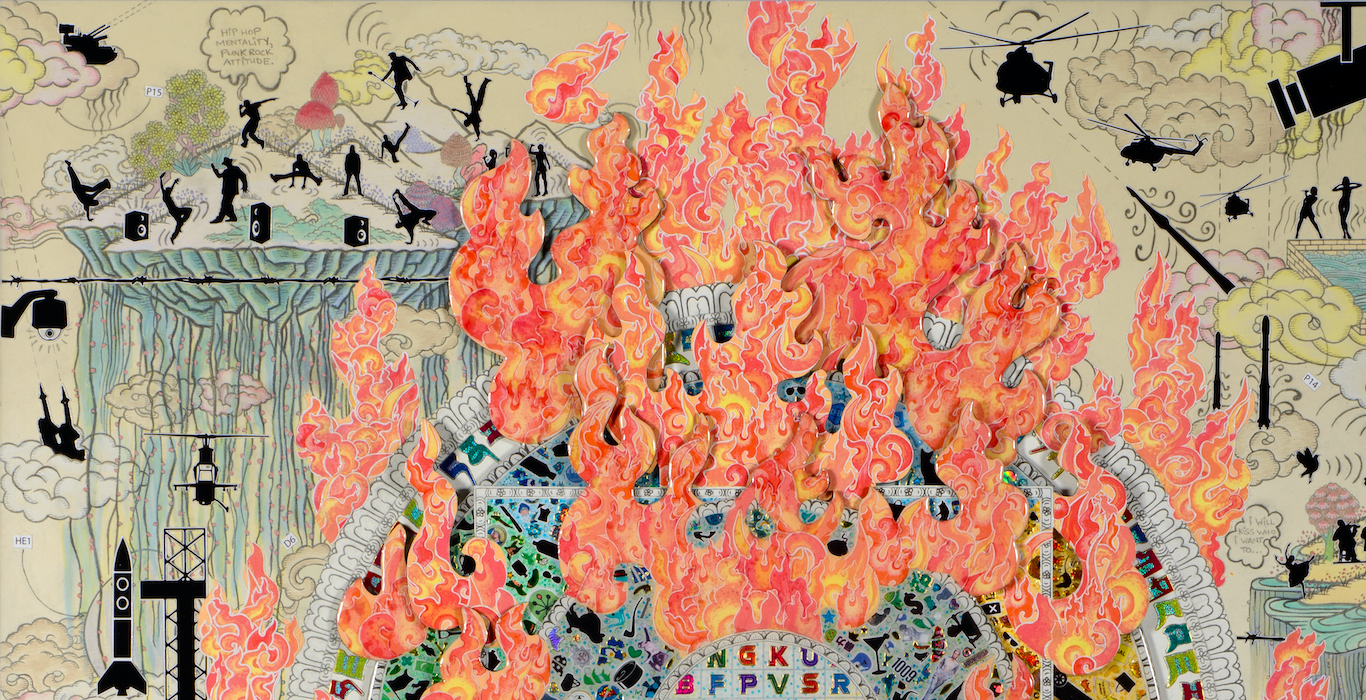

Shangri-La (2014) derives its title from James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon, in which it is described as a mysterious, mythical, utopian Himalayan paradise—a Western fantasy of a timeless, exotic “Orient”. The piece itself provides the viewer with a swift contradiction of its title. It depicts a mandala that reveals an abundance of unexpected imagery the longer one gazes at it: silhouettes dancing animatedly, weapons of mass destruction, animals, Shakespeare, and QR codes—all of it surveyed by the seemingly ubiquitous surveillance camera. Speech bubbles emerge from figures on the periphery containing messages that can be enigmatic, witty, or simply arbitrary. The highly geometric form of the mandala (which, in one sense in Tibetan Buddhism, acts as a symbolic representation of the cosmos) is engulfed in flame—both a destructive threat to the work’s geometric harmony, and a promise of purification for the symbols of capitalist excess it is surrounded by.

Luke Heng

Singaporean artists Luke Heng (b. 1987) has an extremely multifaceted body of work despite his young age. His interests include Ancient Chinese medicine, painting as a process and as a medium, digital technologies, and eastern philosophy. Over the years, Heng has experimented with various mediums in order to interrogate and expand what constitutes the act of painting. By referencing Greek mythology and ancient Chinese divination texts like I-Ching, Heng’s work is the tether between text, language, and art.

In 2020, Heng received his MA from LASALLE College of the Arts (in partnership with Goldsmiths, University of London) in 2020. His first solo exhibition was held at FOST Gallery, Singapore in 2015. After his second solo exhibition at Galerie Isabelle Gounod, Paris in 2016, Heng returned to Singapore for exhibitions at Mizuma Gallery in 2016 and Pearl Lam Galleries in 2017.

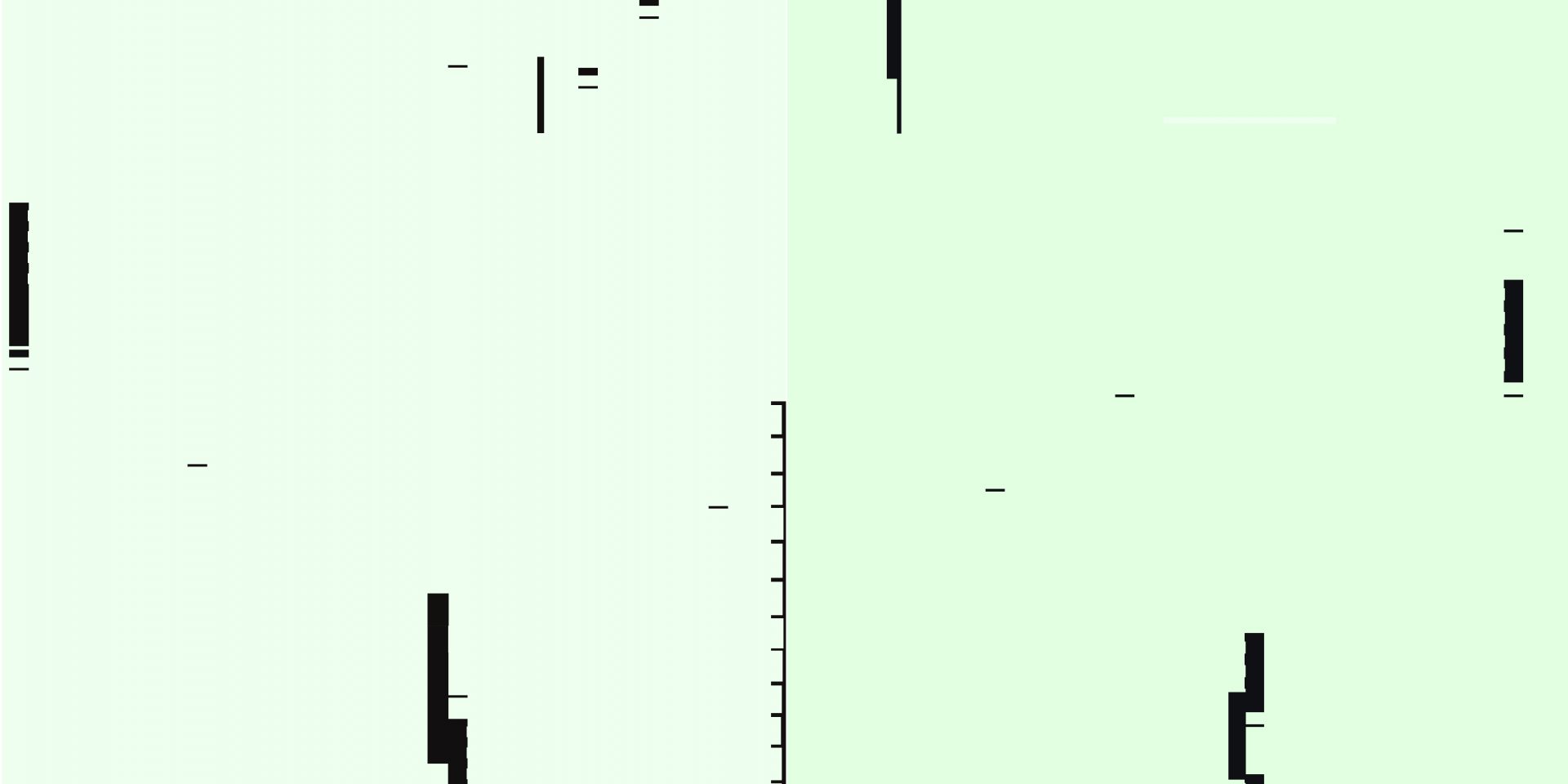

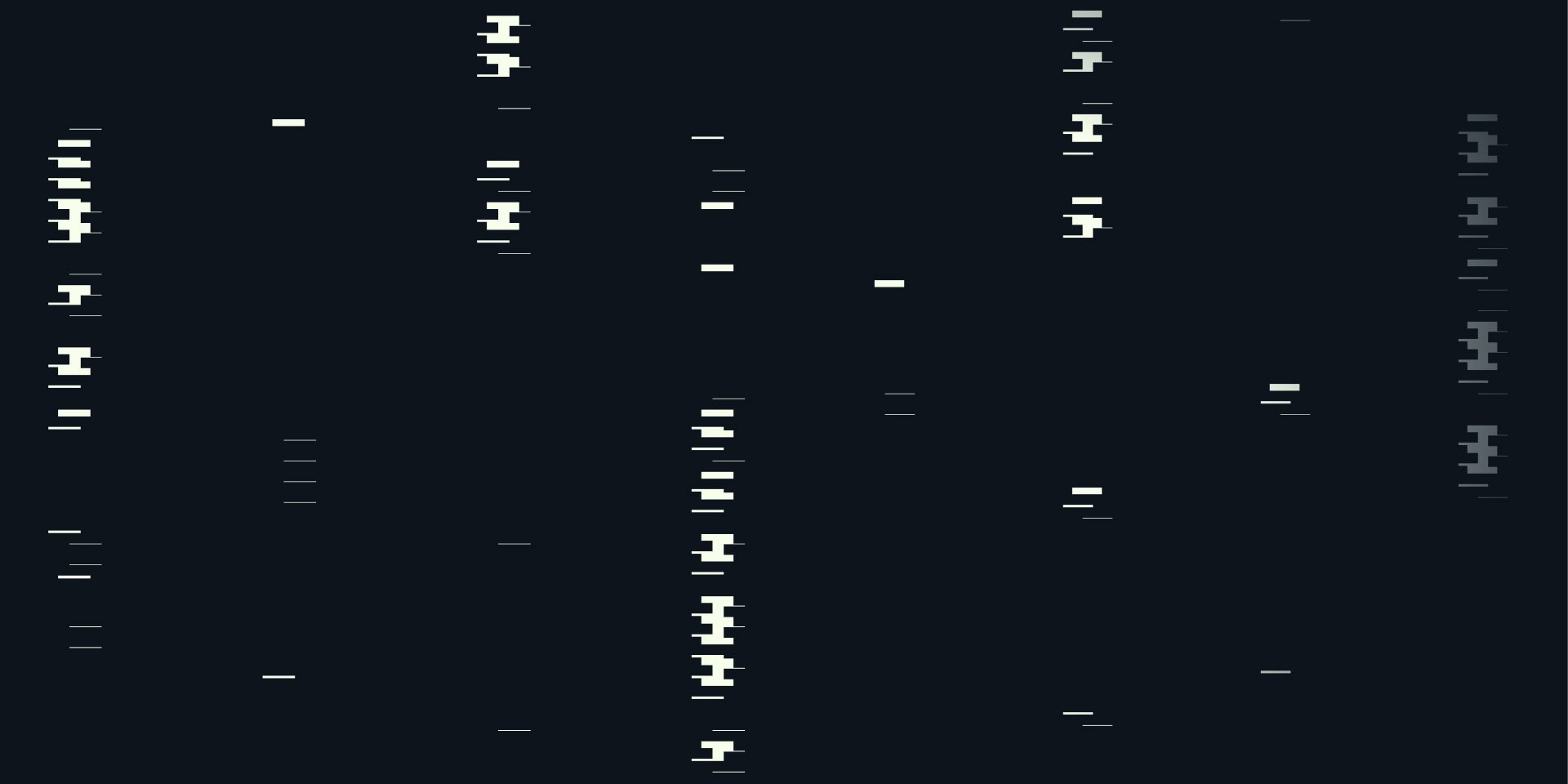

Born to a traditional Chinese physician father, Heng grew up helping around the store, observing these medicinal practices and doctrines. When he first started painting, the artist thought back to how a physician would diagnose his patient–the tone of the skin, the speed of the pulse, the texture of the tongue, the color of the eyeball. He applied this very methodical process to his own painting, focusing on composition, the temperature of the paint, and the speed of the brushstrokes. In the liminal and transient canvases of his After Asphodel series (2017-18), Heng emphasizes these aspects of process over the finished product. The artist researched the Greek myth of the Asphodel meadow, first described by Homer as a place “where the spirits of the dead dwell.” Despite being portrayed in the Odyssey as a dark, gloomy, and mirthless place, the Asphodel Meadow has been envisioned as pleasant and even paradisal throughout Western literary history. Heng is interested in this liminal space in which a soul might exist after the body has passed. The viewer can imagine the canvas existing at the threshold of life and death, on its way to purgatory.

Heng’s ‘Non-Place’ works produce a similar ethereal effect to the After Asphodel series. Each painting was first coated with up to 30 layers of paint before Heng carefully poured turpentine on the surface. The turpentine caused streaks of paint to run off the canvas, leaving elusive voids of color on the surface.

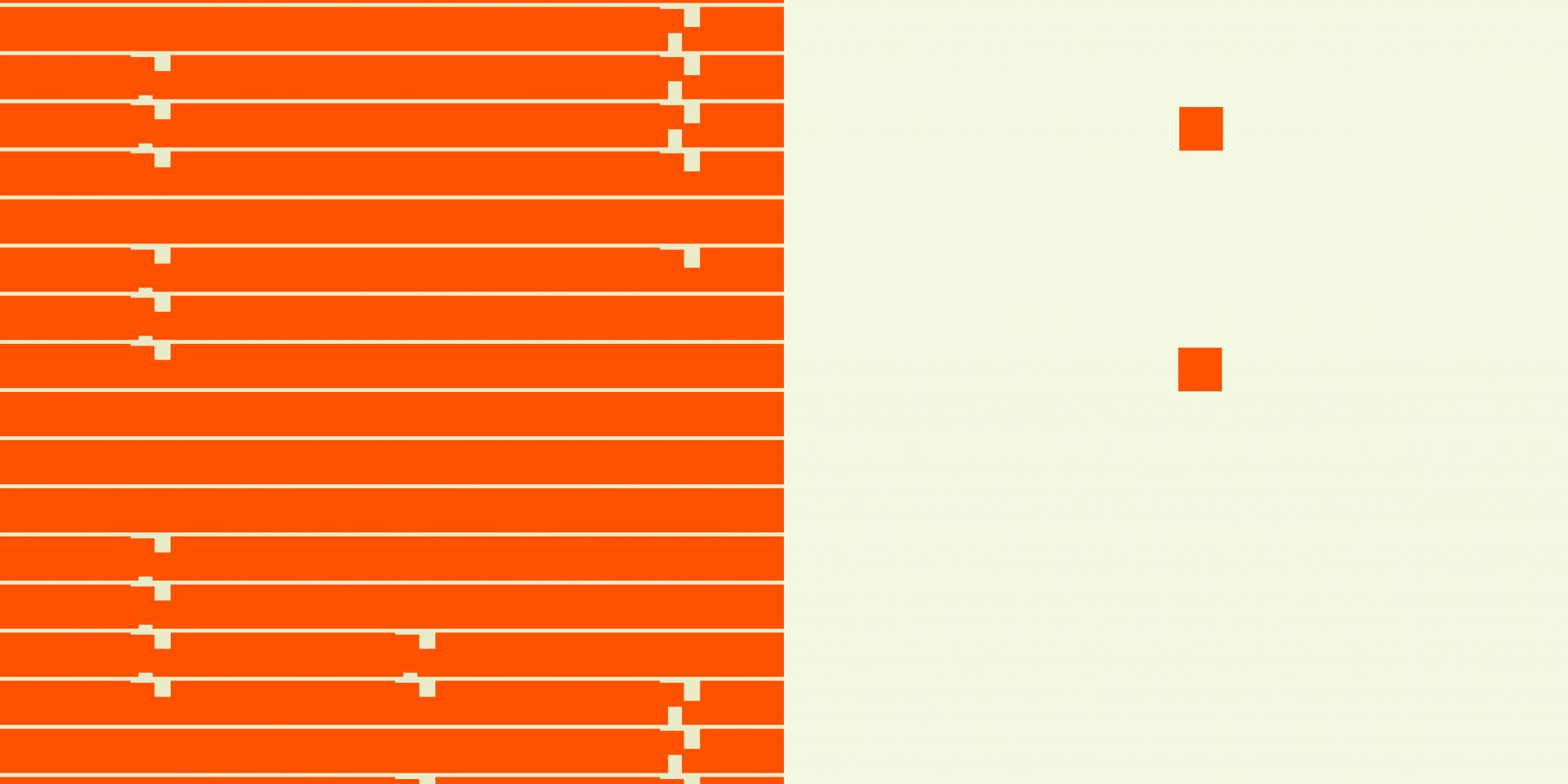

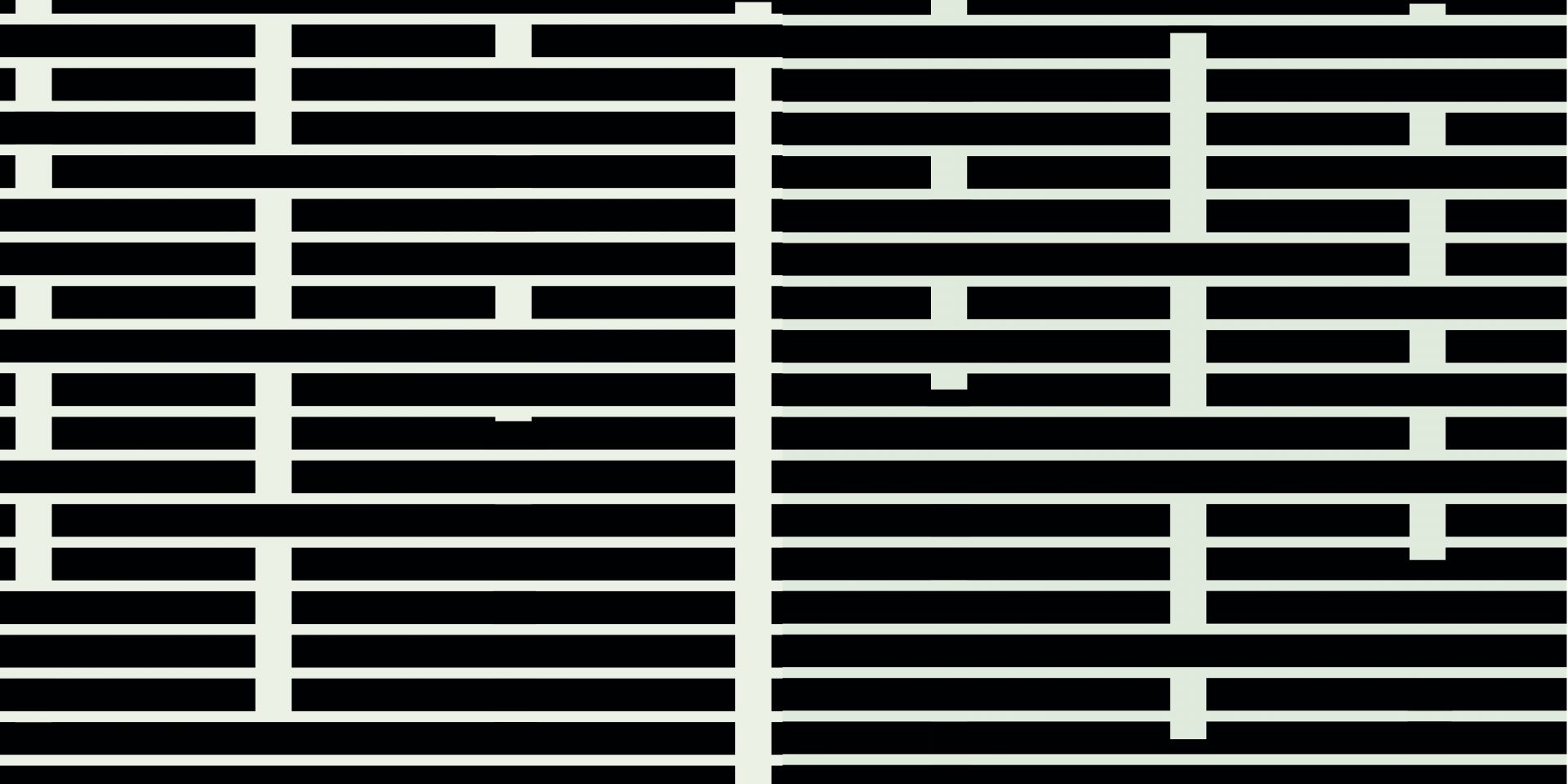

The parallels Heng drew between the doctrine of Chinese medicine and his practice led him to research Yin-Yang philosophy, which then segued into I-Ching (Ancient Chinese Divination text) and Taoism. For thousands of years, the I-Ching has served as a philosophical taxonomy of the universe, a guide to an ethical life, and a fundamental text for Confucian, Taoist, Buddhist, and, even Christian schools of thought. The 64 I-Ching hexagrams–figures composed of six stacked horizontal lines, where each line is either Yang (an unbroken solid line), or Yin (a broken line with a gap in the center)–served as the foundation for his Periodic Seedlings series (2018), currently on view at Appetite.

Each 180 x 180 aluminum square presents a digitally-rendered pattern based on a random assortment of I-Ching hexagrams. These pixelated patterns encourage the viewer to consider language as a constructed series of symbols. The artist broadens painting beyond oil-on-canvas to encompass digital programming as well.

Throughout the rest of his practice, Heng has generally tried to “avoid technology as much as possible.” However, when putting together a slide presentation of hexagrams, the artists came up with the idea for Period Seedlings incidentally. Using an online software to randomly generate an 8 x 8 grid of the 64 hexagrams, Heng created a new kind of visual and digital language based on the I-Ching principle of chance. The artist had very little control over the works and even left the computer software to randomly generate colours. The logistics of printing, condition of the printer, and how to exhibit the works came down to the artist himself, however. Heng relinquishes the control demanded by oil-on-linen and instead embraces randomness and chance.

Heng’s Periodic Seedlings interrogate language as both a system of symbols and language as a means of communication. He utilizes the I-Ching hexagram as the atomized unit of a visual language. His minimalist After Asphodel and Non Place canvases are studies on what defines painting and possibilities of the medium, where it could go and what it could be. Much like the Yin-Yang philosophy that influences Heng, his body of work is a duality existing in harmony–one side embracing digital intervention while the other harking back to the fundamental elements of painting to interrogate what defines, limits, or expands this artistic process.

FX Harsono

Indonesian multi-media artist FX Harsono (b. 1949, East Java) has made a career of reconstructing histories and addressing unspoken realities. His artwork speaks loudly and profoundly for those who have found their voices silenced. In a country that was ruled by dictatorship for most of his life, Harsono’s work never fails to push socio-cultural — and legal — limits. On top of many solo and group shows across Indonesia, Harsono’s work has been featured in exhibitions across the world, including at the 20th Biennale of Sydney (2016), the 4th Moscow Biennale (2011), the Singapore Art Museum, and the Asia Society Museum in New York City. In 2014, the artist was awarded a Prince Claus Fund Laureate Award, followed by the first Joseph Balestier Award for the Freedom of Art, awarded by the United States Embassy in Singapore and Art Stage Singapore in 2015. He is represented by Australian gallery Sullivan + Strumpf.

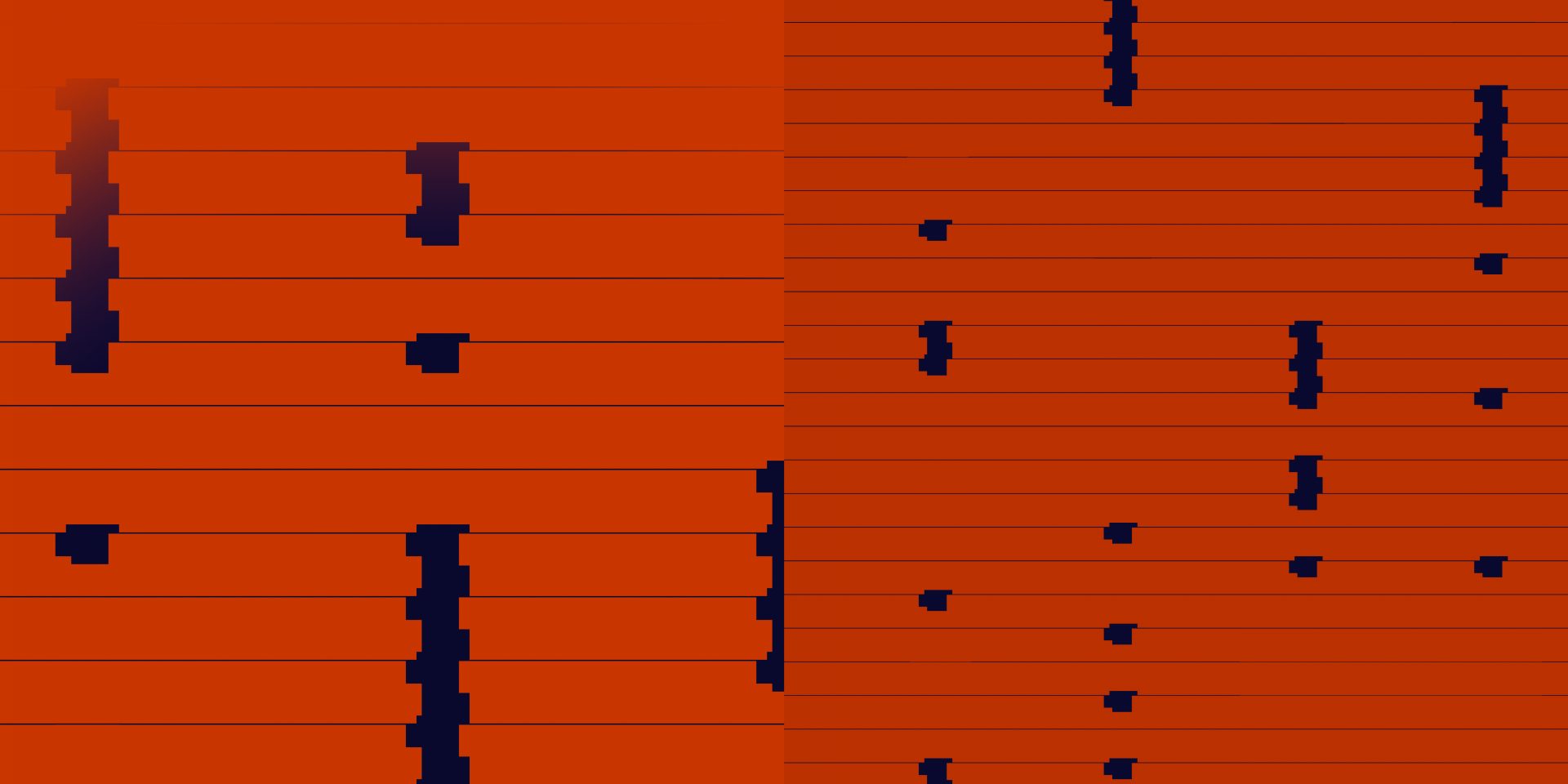

FX Harsono

Writing In The Rain 1-4, 2020

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminium panel

40 x 65 cm each – set of 4

Edition 3/10

Sullivan+Strumpf Gallery

FX Harsono

Writing In The Rain 1-4, 2020

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminium panel

40 x 65 cm each – set of 4

Edition 3/10

Sullivan+Strumpf Gallery

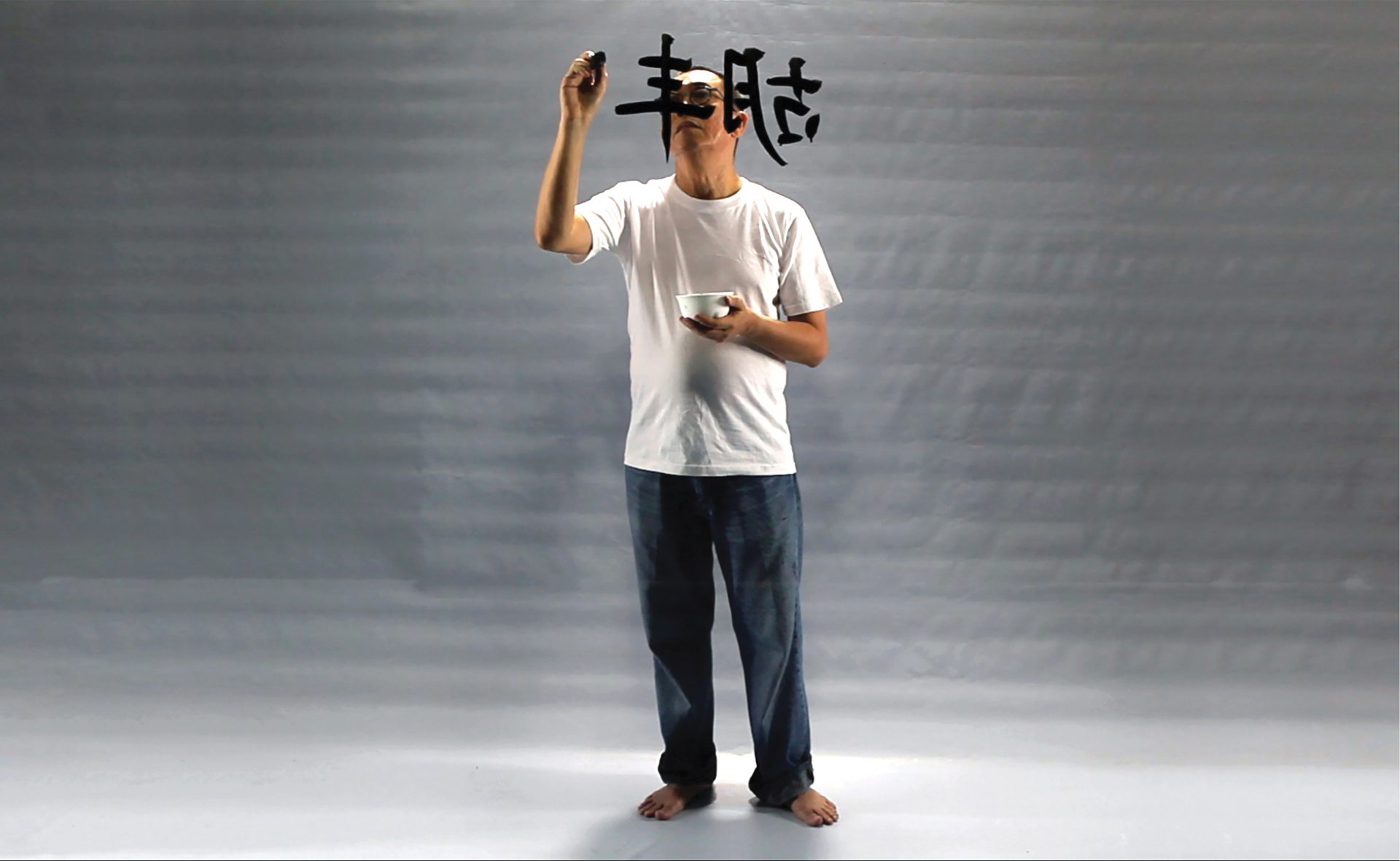

Writing in the Rain, 2011, is a testament to the ongoing battle by Chinese Indonesians for remembrance. It has been shown at Tyler Rollins Fine Art gallery in New York, and in 2018, across all of the video screens in Times Square. In the video, Harsono writes and rewrites his Chinese name — “Oh Hong Bun,” in the Hokkien dialect, or “Hu Feng Wen” in Mandarin — in Chinese calligraphic letters. The characters in his name are the only ones he remembers. After painting several iterations of his name on a glass wall, water begins to pour down and wash away his calligraphy. Harsono continues with the act of writing, each brushstroke of ink now seemingly undoing the mark making from before. From writing to erasure, he stands in a pool of black ink, still persisting, but only the faintest evidence of his Chinese name remains.

It is a fight to reclaim one small shred of his Chinese heritage, having been forced to change his name to an Indonesian one at age 18. Under the Sukarno and Suharto dictatorships, assimilation laws forced Chinese Indonesians to give up their traditions, their religion, and their language. Writing in the Rain is an intimate meditation on loss and erasure: In the words of Tyler Rollins, “Harsono is able to touch on concerns that resonate globally, foregrounding fundamental issues that are central to the formation of group and personal identities in our rapidly transforming world.”

A shout out to our research team:

Kathryn Miyawaki

Sabrina Cunningham

Maddie Rubin-Charlesworth

And a very special thank you to:

Pearl Lam Galleries

Mizuma Gallery

Sullivan+Strumpf Gallery

A+ Works of Art

National Arts Council (NAC)