The Order of Things

The symbol is an object of the known world hinting at something unknown – Aniela Jaffé

Symbols have long been a source of fascination and mystery. Modern day researchers puzzle over the symbolic significance of architectural ruins, the coded gestures of iconic figures depicted in art, and motifs that recur in different cultures across time and space. Often associated with ritual and the metaphysical dimension, many symbols carry with them a psychic charge that hint at pathways to other realms – a different order of things beyond the purely objective.

The enigma and power of the symbol is always in the fact that it is much more than what it immediately represents. Symbolism engenders rich readings beyond that which is depicted ‘on the surface’, and its allusive qualities are well suited to allegory and metaphor. By yoking idea to image or object, symbols function as visual systems of meaning – powerful narrative vehicles that communicate shared human codes, urges, patterns, values and traditions.

The Order of Things brings together the work of five artists who employ symbolism in their art. Drawing on images and patterns that are by turns culturally specific, deeply personal and hauntingly familiar, these artists reanimate iconography referencing spiritual and cultural traditions to speak to contemporary contexts; to order, or re-order, our experience and understanding of the world. The origin of the word ‘symbol’ – the Greek word symballein, meaning ‘to throw together’ – refers to the ritualistic reunion of broken tokens (rings, bones) to renew alliances and connections. In the same way, these symbols, or what Carl Jung has referred to as “innate, inherited shapes of the human mind”, connect us across time and space, to a deep reservoir of a shared, collective unconscious and understanding – an order of things beyond the present, and intelligible experience.

The Order of Things is open to public from 16 May – 19 Aug, 2023.

Adam de Boer

An artist of Dutch-Indonesian heritage, Adam de Boer was raised (and identified) as ‘American’ for most of his life. A Fulbright scholarship brought him back to Indonesia where de Boer seemingly made up for lost time by immersing himself in the study of Indonesian art forms, such as batik painting, woodcarving and wayang kulit, in an attempt to reclaim his hybrid identity and come to terms with the displacement he inherited as a diasporic artist. Much of his recent work treads between disparate cultures, creating relations between images and figures from distant lands by strategies of homage and appropriation.

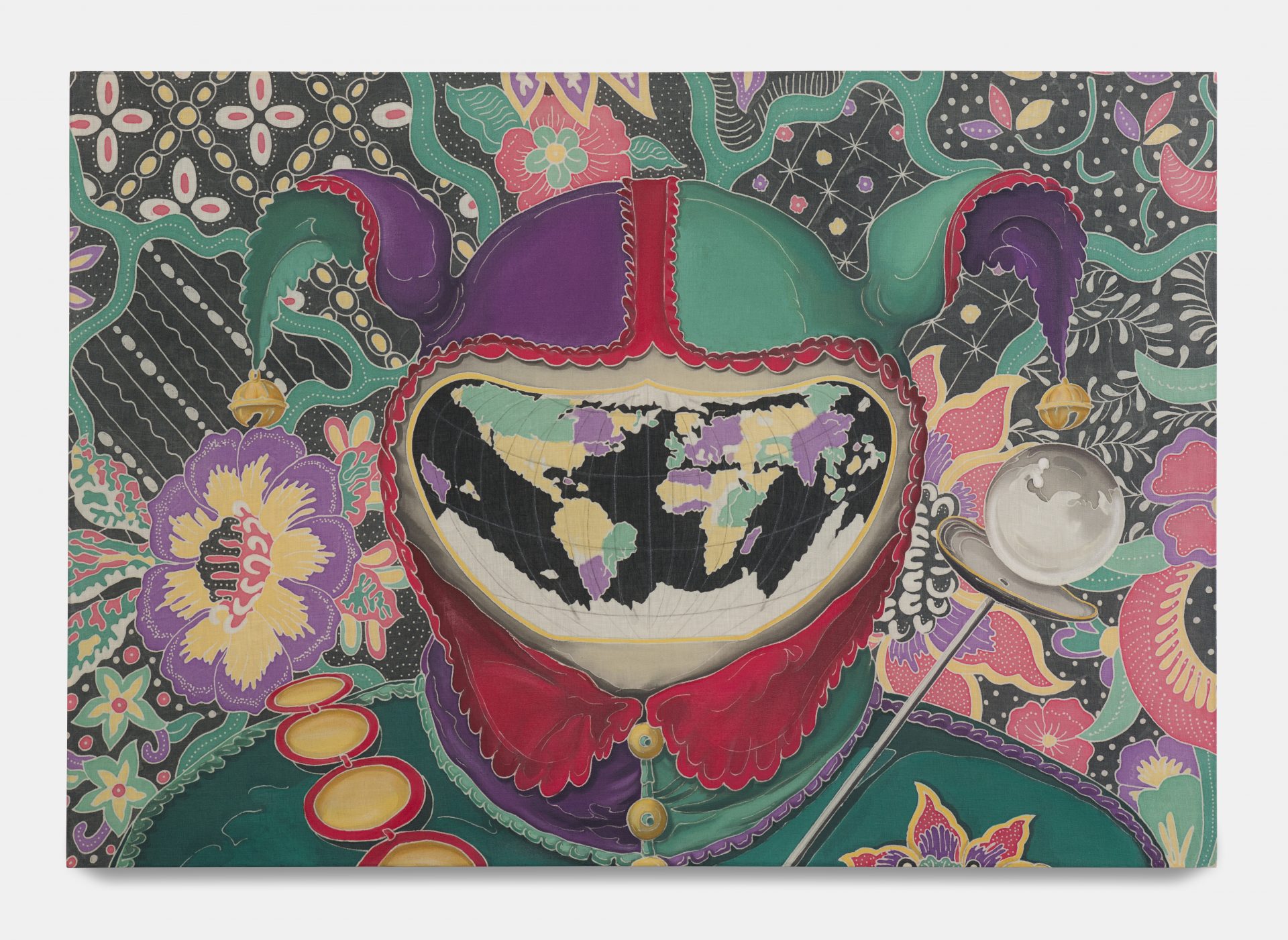

The fourth iteration in a small series of Fools Cap Map paintings, this densely layered work beguiles the eye with its profusion of patterns and imagery. De Boer’s painting is a fairly faithful rendition of an enigmatic image from late 16th century Europe – the age of conquest of the New World. Known to cartographers as the Fool’s Cap Map, the image comprises a map of the world placed in the visage of a jester’s cap. The Fool, or court jester, was the only figure licensed to critique the powers-that-be, often speaking hard truths in the form of riddles bordering on the ridiculous. As such, the fool is symbolic of subversion and an overturning of hierarchies, leading to a reading of this image as an implicit critique of how the world has been ‘mapped’, and suggesting that “all seemingly universal truths, all apparently trustworthy knowledge or authoritative maps, are partial and untrustworthy in that they conceal a hidden social ordering”.

De Boer has layered an additional narrative on top of this primary image, with the inclusion of a batik motif background and the employment of batik painting techniques to render this work. Far from being merely decorative, each motif in this traditional Indonesian art form is deeply invested with meaning and symbolic significance. The patchwork pattern visible in the background of Fool’s Cap Map of the World no. 4 is known as the sekar jagad motif: translated, this could mean ‘flowers of the universe’ or ‘map of the world’. It has been noted that this motif resembles an interlocked archipelago, with each patterned island retaining its distinctive identity whilst embracing its neighbour, read as a metaphor for the beauty of Indonesia’s diversity, and by extension, that of the larger world. Here then we have two markedly different visual registers in dialogue, each encoding the world / cosmos within distinct iconographies and visual forms, and each proposing a different ordering of the world.

Savanhdary Vongpoothorn

Savanhdary Vongpoothorn’s family fled Laos for Australia when she was but a child. While there is some degree of estrangement from the culture of her country of origin, Vongpoothorn’s travels through Asia as well as the connections forged through her parents shaped her affinity with the region’s spiritual and aesthetic traditions. Her intricately patterned canvases draw on a variety of visual languages and aesthetic conventions reflective of her life and artistic journey, bringing together, for instance, elements from Western formalism and abstraction, Laotian textile design, diagrammatic representations of Buddhist concepts, and a repetitive, all-over perforation and patterning that recalls meditative practice as well as the sacred constellation of dots used in Aboriginal art.

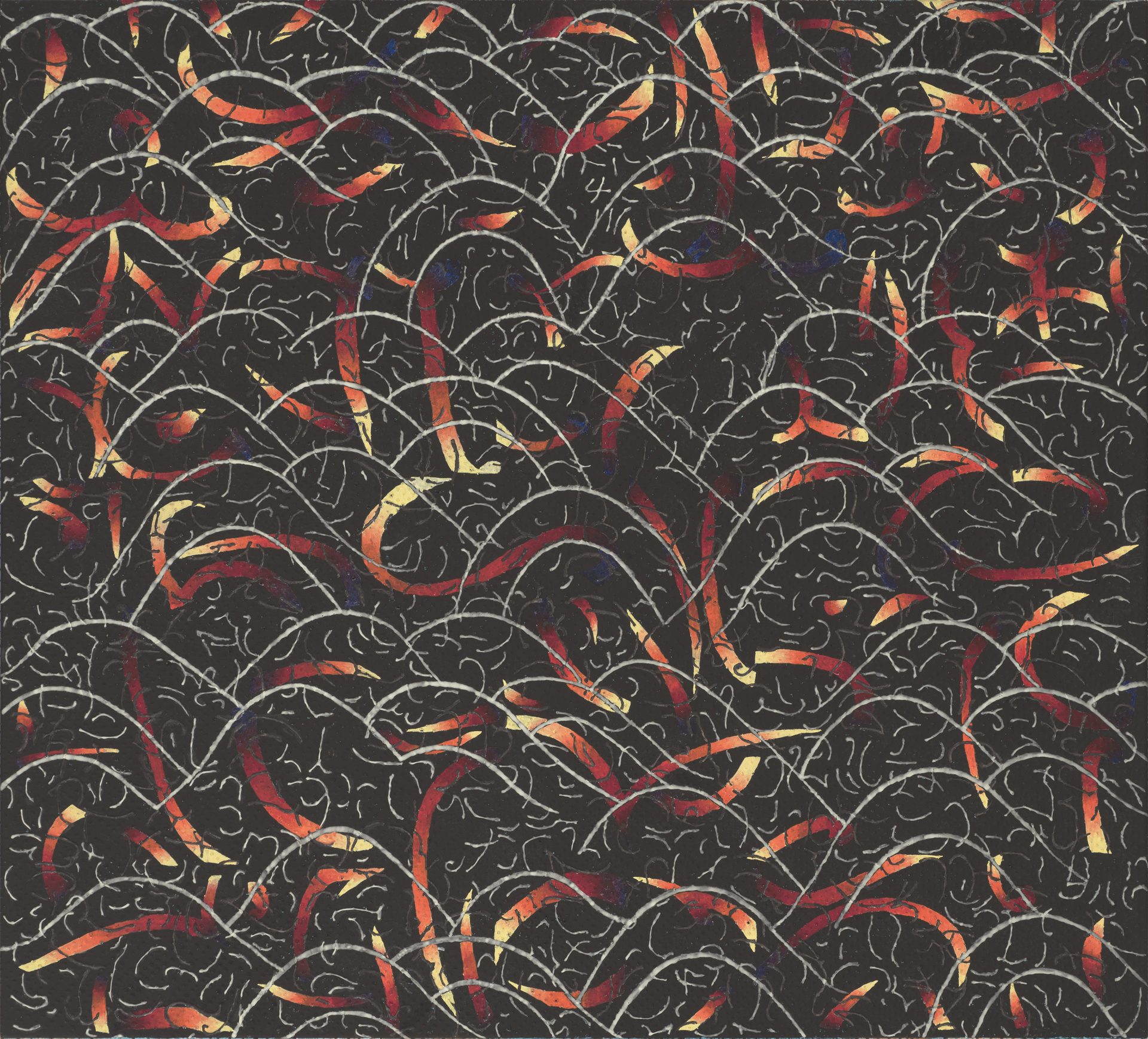

Presented here are two recent works that express different poles of human experience and existence. In Sea of Fire, ribbons of vermillion dance across a pitch-black background, overlaid by broken, agitated calligraphic gestures as well as rhythmic wave-like patterns. The sense of disquiet here is palpable, even before one reads the artist’s statement about the motif being inspired by her family’s experience of the Black Summer bushfires of 2019 and 2020 in Australia – catastrophes further compounded by floods and the pandemic. The fire motif also references the Fire Sutra, or Fire Sermon, a Buddhist text in which the Buddha preaches about achieving liberation from suffering through detachment from the five senses and mind. The fragmented marks on Vongpoothorn’s canvas hint at the broken path we have to these Buddhist teachings of enlightenment; however, they remain constant, and unwaveringly illuminated even in moments of darkness.

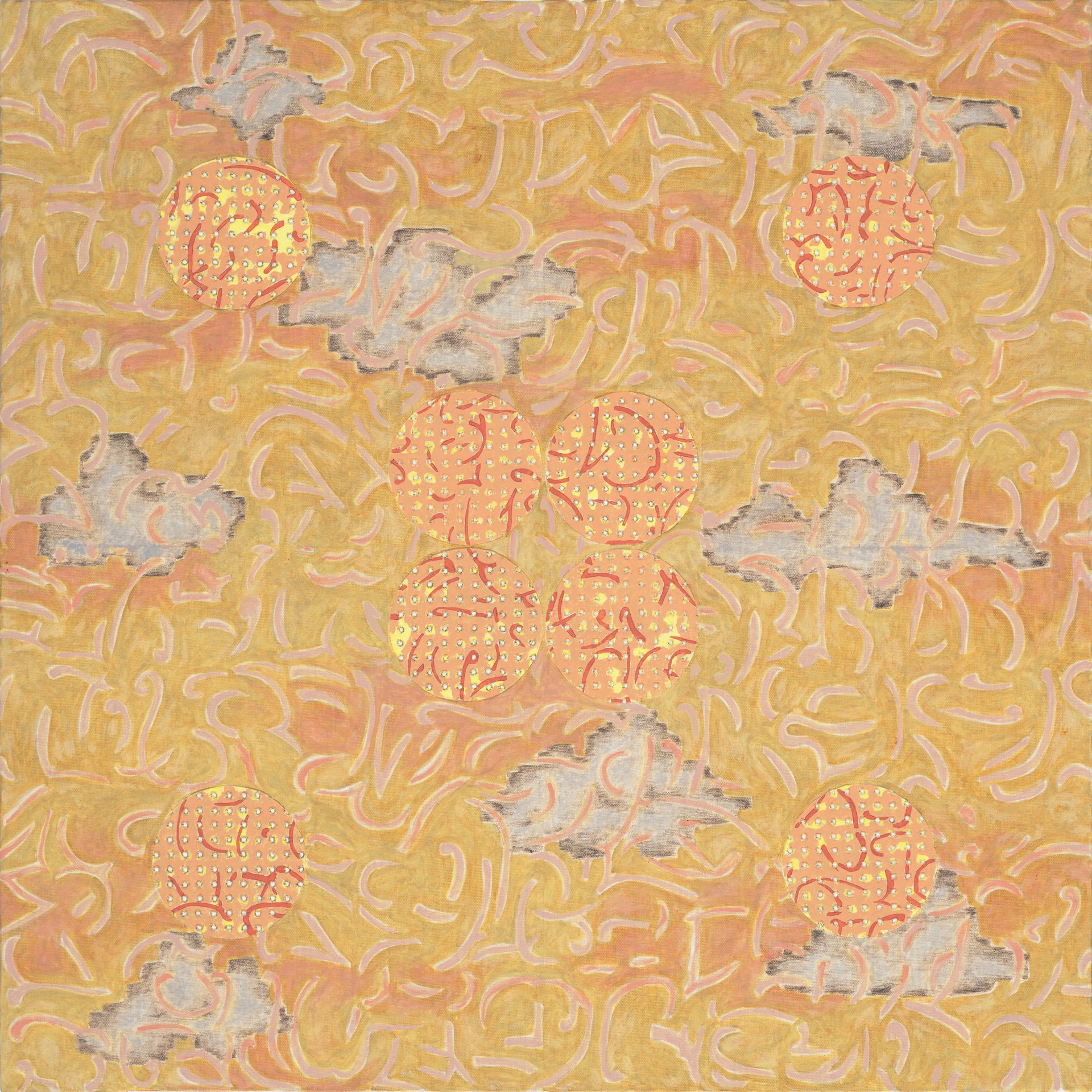

Quincunx and Clouds I on the other hand, expresses a sense of harmony and repose. Clouds for Vongpoothorn are symbolic of the passing of time and the impermanence of life and all things that humanity values and ceaselessly strives for, while the quincunx – a motif commonly encountered in temple architecture – symbolises balance and wholeness: the interconnectedness of all things in an ordered universe. The glowing saffron hues of this painting recall Buddhist monks’ robes, but also represent, for the artist, the illumination of the mind. All these elements are united by Vongpoothorn’s rhythmic calligraphic strokes that dance across the surface of the canvas, enmeshing elements of the material and spiritual world in lyrical equilibrium.

Hasanul Isyraf Idris

Valley of Unity belongs to a body of work embarked on by Hasanul Isyraf Idris during a particularly trying time in the artist’s life, when he was mourning the passing of a number of family members. It was during this period that he encountered in a bookshop a copy of the Persian poem “The Conference of the Birds” (Mantiq-al-Tayr). Birds have long been associated with religious symbolism, given their capacity for flight and ascent. Written in the 12th century by the Sufi poet and mystic Attar of Nishapur, “The Conference of the Birds” is an allegory of the soul’s journey towards the divine, narrated through the quest of the birds of the world for the mythical Simorgh, the bird-king. In order to reach the Simorgh, the birds have to cross seven valleys, each of which presents a moral or spiritual test that prepares the birds for their final encounter with the Simorgh. Several birds perish as they cross the valleys, and at the end of the quest, only thirty birds remain. This group of thirty are told to look in a pool of water to find the Simorgh, and in doing so, they encounter their own reflections, and the realisation that they are the Simorgh (translated, ‘Simorgh’ also means ‘thirty birds’). “The Conference of the Birds” thus teaches that the Divine is in each and every individual – one in many, and many in one.

Named after the fifth valley in “The Conference of the Birds”, where the birds learn that everything is interconnected, this painting gives vivid form to the symbolism of the poem whilst weaving in commentary on contemporary issues. A group of birds gathers around a giant nest – a resting place, where one can seek solace. In between their brightly-coloured plumage, one catches glimpses of sushi bento boxes, alluding to the contemporary culture of consumption, in particular fast food culture. This is reinforced by the inclusion of the bird figure on the right, perched on top of a stack of instant noodles and snacks. A decorative border frames the central image – an allusion to the aesthetic conventions of illuminated manuscripts – but a closer look reveals this border to be a never-ending loop of consumables, akin to the conveyer belt of sushi restaurants, designed for insatiable appetites and instant gratification. In these margins, Hasanul has devised an iconography for our times: an inhaler-gun for when we are out of breath, sushi soya sauce for taste, butter (fat) to sustain life, and a shimmering compact disc to represent light or divine illumination – collectively, contemporary symbols for flesh and spirit.

Albert Yonathan Setyawan

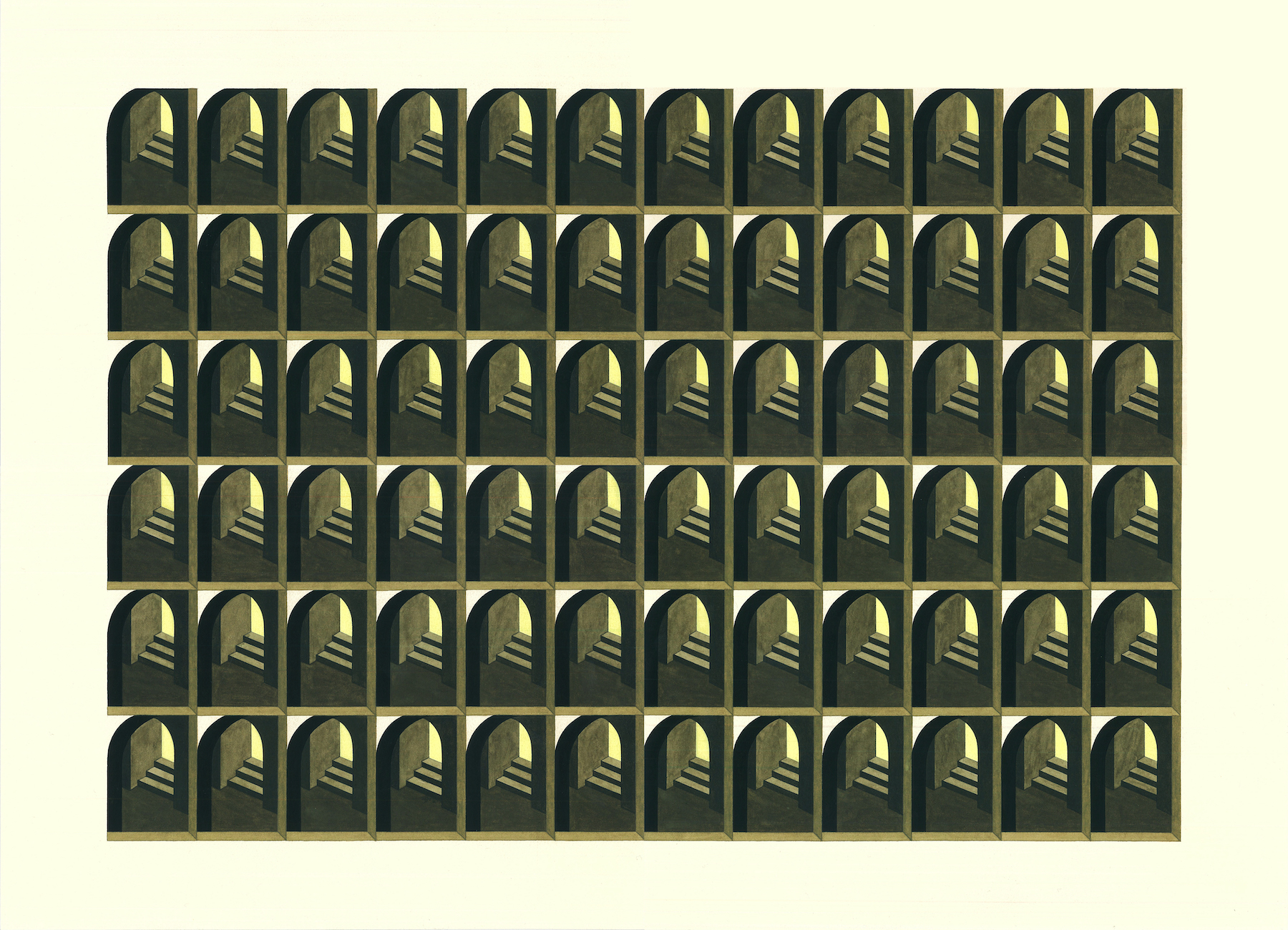

Working primarily between ceramics and painting, Albert Yonathan Setyawan conjures intimations of other worlds and orders through the use of pattern, repetition, and the language of symbolism. There are two discernible strands of imagery in his practice, the first revolving around architectural structures or spaces – such as stupas, archways, windows and stairways – and the second comprising a vocabulary of symbolic forms created by the artist.

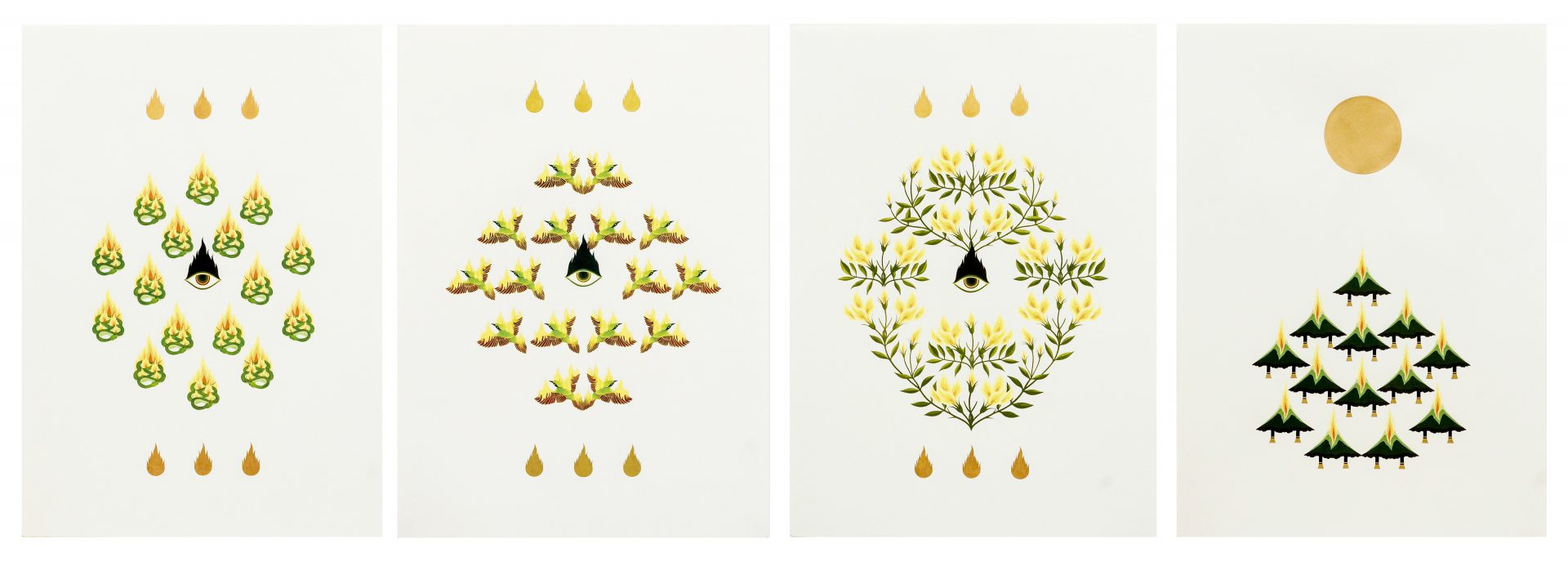

In the latter, we find enigmatic symbols that may be perceived as having some sacred quality, comprised as they are of images that are already invested with mystical associations across various cultures: fire, birds, the eye, serpents, flowers. Many of these symbols are often ambiguous, having auspicious connotations in some cultures and the opposite in others. Interestingly, they transcend time and geography, stirring in us an unconscious recognition of their power and enigma. Drawing on conventions of Hindu and Buddhist art, such as ideas of multiple emanation and the mandala, Yonathan often arranges his images in a repetitive and / or circular formation, instilling in viewers a meditative quality, and restoring us to a time when images were powerful and sacred, holding within them mysteries and worlds beyond the order of rational comprehension.

Yonathan’s Hypnagogia series was inspired by his experience during the pandemic, when he spent much of his time isolated at home. In this body of work, quotidian spaces within the home, such as windows, ceilings and staircases, are repeated to hypnotic effect. The intersection of spaces between each image in turn creates ambiguous and contradictory spaces, akin to a hallucination, or the transitional state of consciousness between wakefulness and sleep referenced in the work’s title. The repetition invests these otherwise mundane vignettes with a symbolic and uncanny quality – uncanny in the truest sense of its original German term, unheimlich, meaning ‘unhomely’. The ensuing sense of dislocation and disquiet bears some similarity to the surreal stillness of de Chirico’s paintings, with their portentous cityscapes hinting at some impending rupture. In the words of psychologist Aniela Jaffé, these are “dreamlike transpositions of reality, which arise as visions from the unconscious”. The liminality of sleep/wakefulness is that sliver between one order of things, and another.

Udomsak Krisanamis

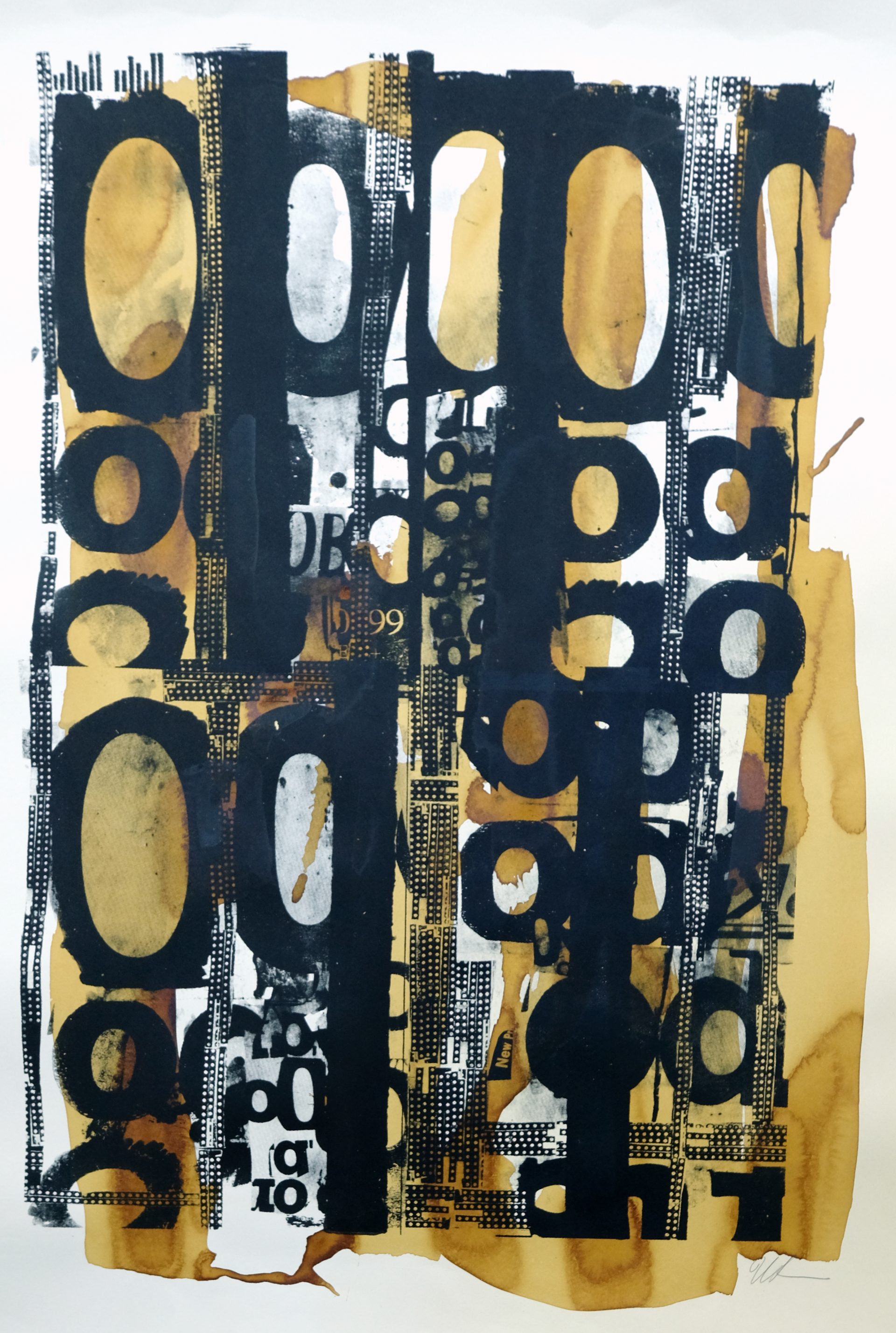

Several artists have, over the course of their career, developed particular visual motifs that grow to hold special symbolic significance. For Udomsak Krisanamis, this is clearly manifested in the repetition of the O shape in his works, and its evolution over time both as a visual element, as well as a signifier. Born in Thailand, Krisanamis moved to the United States to study at the Art Institute of Chicago, before settling in New York for a time. As an art student struggling to learn English, Krisanamis would tackle the newspapers with a marker, blacking out words he already recognised and circling those he did not, thus mapping out the gaps in his understanding, and imposing some kind of order in an unfamiliar environment. Over time, this exercise would extend to doodling, where the artist would black out all text, leaving only the empty centres of the letters O, 0, 9, and P, or what typographers refer to as the ‘counter’. These empty voids, loops, and black bars became distinctive elements in Krisanamis’s art, as he collaged and layered them to varying effect and rhythms, often combining newsprint with other everyday objects that reflected his life and environs, such as instant noodles, flyers, and packing tape. Notoriously reticent about his work, Krisanamis has insisted that ‘what you see is what you get’, leading critics to read these abstractions – born out of the artist’s quotidian exercise in ordering his world – as references ranging from twinkling cityscapes to satellite imagery and binary code. These circular voids, which lend themselves to more transcendental interpretations, are however, always grounded in the personal, and the immediacy of their maker’s environment, for instance with the incorporation of coffee paint in the making of the work Mind Drifting. Krisanamis’s works exemplify art writer and critic Jennifer Allen’s proposition that symbols in art are compelling because they present “the possibility of artworks being visible, intelligible yet somehow cryptic and personal.”

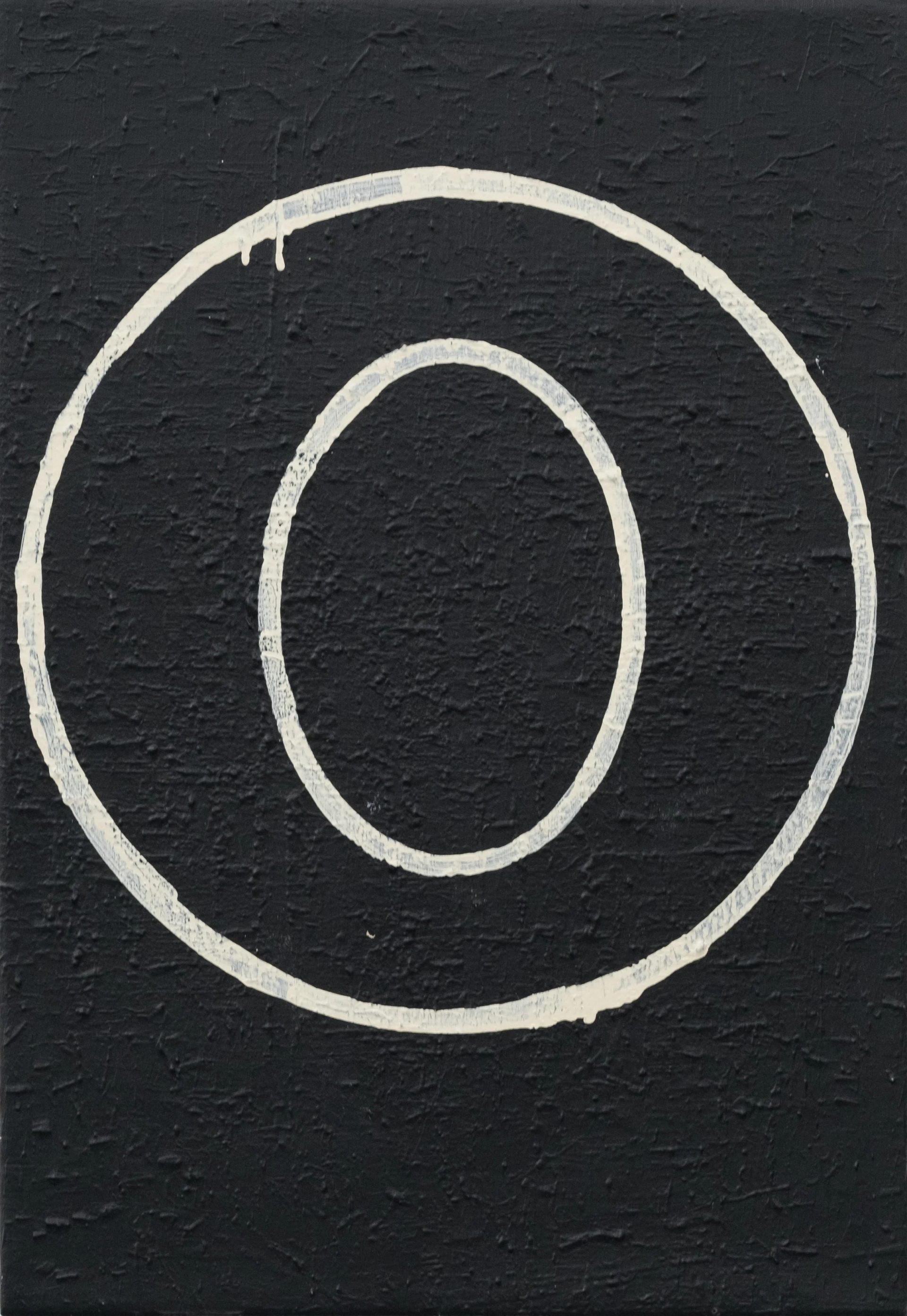

In Clear The Air, executed a decade later, Krisanamis’s signature motif has been simplified, the dense, repetitive layering of earlier works distilled into two circular shapes which look like they have each been rendered in a single stroke, a nod to the Ensō paintings of Zen art. An enduring symbol that has recurred throughout time and across cultures, the circle represents completion and wholeness. At the same time, it is also zero – nothingness, space, and void. The underpinnings of this image are however, rooted in the quotidian. The texture on the canvas comes from the artist’s layering of newspapers – a nod to the beginnings of his practice – and the spheres have in fact been traced from everyday objects: a bicycle wheel and an oval photo frame. Krisanamis’s enigmatic image, in its spareness, lends itself to a multitude of significations, shifting between the invocation of a cosmic order, and the order of everyday things.

Curated by:

Tan Siuli

With thanks to:

Seet Yun Teng

Damon Lim

Jocelyn Lui

39+ Art Space

Gajah Gallery

Gallery VER

Mizuma Gallery

Richard Koh Fine Art