What Happened Here?

Appetite is proud to presentWhat Happened Here?, a meditation on memory and land. The show brings together five artists—Ricardo Mazal, Lindy Lee, James Jack, Sim Chi Yin, and Yang Yongliang—who strive to uncover layers of memory, truth and loss from the fabric of the earth.

Materially and conceptually, these artists reveal how our memories are structured by and within the landscapes we inhabit. What impurities, truths, and omens are imbedded in the land we see before us? How has it shaped the way we have remembered and will remember going forward? This show is open to the public from May 4, 2021 — July 26, 2021.

Ricardo Mazal

Mexican contemporary artist Ricardo Mazal (b. 1950, Mexico City) investigates the ephemera of spirituality by grounding it in the real. Through his particular process of abstraction, Mazal fluently renders his own experiences of sacred sites in vivid color and geometry. His work resides in the private collections of institutions such as the Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City; the Americas Society, NYC, the Maeght Foundation, Saint-Paul-de- Vence, France, and the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Arizona. Mazal has also been the subject of solo exhibitions across Latin America, Europe, Asia, and North America, including Full Circle, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, NYC (2020), Violeta, Museo Estación Indianilla, Mexico City (2017), and Kailash Black Mountain, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, Hong Kong, China (2014). He currently lives and works in Santa Fe, New Mexico and New York City.

Mazal’s body of work attests to a deep interest in the physical sites and cultural situatedness of burial rituals around the world. Most notable is his “Trilogy of Burials” project, which spans a decade and three continents. In seeking to experience and document the different ways we lay our dead to rest, he has traveled to ancient tombs inside pre-Hispanic ruins in Chiapas, Mexico; to Germany’s Odenwald mountain range where new, alternative methods of burial in the forest are growing; and to Mount Kailash, Tibetan Buddhism’s most holy mountain— the center of the universe and the axis upon which the world turns. Here he has witnessed the traditional practice of sky burials, wherein the deceased’s body is laid out on the mountainside to be consumed by scavenger birds. For Mazal, the act of pilgrimage is a personally constructive one— and an endeavor that catalyzes his particular process of abstraction.

Mazal’s rigorous process solidified during the Tomb of the Red Queen project, when he noticed a similarity between his site photographs and his previous work. Inspired by these intersections, he developed a distinct artistic routine that involves digitally manipulating and collaging his site photographs for months before creating a painting. The resultant transmuted images serve as the visual basis for his energetically rendered oil paintings, where striated swathes of color can convey the movement and energy of prayer flags just as powerfully as they do the sober timelessness of a graveyard. Mazal’s highly involved procedure is a transmedial one which seeks to merge a landscape’s reality and abstract spirituality into a greater whole. The result is a body of work where each piece is charged with distilled, concentrated experience— an image of a memory still imbued with the trappings of feeling.

Violet Red 2 and Green and Payne’s Grey 2 are from Mazal’s “Violeta + Bhutan” works, in which the artist unites two of his most prominent series to conduct an expansive study on colour. Distinct from most of his practice, “Violeta” grounds itself solely in the intangible; its conceptual basis lies with music, emotion, and the contemplative state that can be generated by pure color. Meanwhile, “Bhutan” is borne out of Mazal’s journey to the country’s mountainous landscape, and his fascination with the vitality of the region’s distinctive prayer flags. Colour is paramount to the intent of each flag; each one has its place in a canon of symbolism meant to aid in spiritual thought and action. With Violet Red 2, Mazal fluently brings together two modes of color study into a single canvas, resulting in a warm expanse of pigment, both hazy and sharply defined. Green and Payne’s Grey 2 evokes the organic shades of the natural world, with subtle striations and differing degrees of saturation materialized into an image that resembles tree rings or rock strata just as easily as it does the textures of woven fabric. Mazal’s abstract method serves to clarify seemingly diametric aspects of experience—introspective exploration and embodied encounter—and show they are not so dissimilar after all.

Mazal’s devotional study of funerary sites across the globe presents space for meditation on the intersections between land, mortality, and remembrance. His abstracted landscapes draw our attention to the ways in which the earth can serve as a medium of collective memory. While practices of final disposition may vary widely across time, place, and circumstance, all serve to commemorate lives lived and anchor them in the memories of those left behind. By offering us scenes of the different ways we live alongside our dead, Mazal asks us to look for ways that the earthbound condition of these places may actually beckon us closer to the cosmic.

Lindy Lee

Chinese-Australian artist Lindy Lee (b. 1954, Australia) draws from her lifelong journey in search of belonging and her interest in the spirituality of land. Lee was born in Brisbane, Australia, to parents who had immigrated from China, and much of her work reflects the difficulties of growing up in a country where whiteness was the expectation. Her other works address more universal questions around spirituality and humanity’s connection with the natural world, drawing from Buddhist principles such as meditation and the ephemerality of nature. Lee’s explorations of heritage, diaspora, and faith have situated her among Australia’s most acclaimed contemporary artists. Her work has been exhibited in Canada, China, Hong Kong, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand. and Singapore. The artist recently showcased a major survey of her work, titled Moon in a Dew Drop, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Other solo exhibitions include Lindy Lee: The Dark of Absolute Freedom (2014) at the University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane, and The Seamless Tomb (2017) at Sullivan+Strumpf.

Faced with the rise of Communism, Lindy Lee’s parents fled China during the mid-20th century. Consequently, Lee was raised during the tail end of the White Australia Policy— a set of racial laws aimed to bar people of non-white-European descent from entering the country. The policy especially targeted Asians and Pacific Islanders, and as such, Lee was taught from a young age to “act as white as possible” upon leaving the house. Pervasive racism meant that the artist never felt quite at home being Chinese in Australia. Moreover, as she was unable to speak Mandarin, Lee felt equally alienated upon visiting China. “It was actually pretty painful,” she explains. “You always want to belong, you just do.”

As a result, in Lee’s early artistic career, she sought to situate herself among the Western canons of art. She sourced well-known images from art history textbooks, photocopying portraits by Rembrandt and van Eyck. These earlier, portraiture-based works were revealing to Lee— the act of photocopying, in particular, highlighted the artist’s cultural distance from the West. “The copy is the story of me and so many others,” she explains; copying European traditions and artworks was a surface-level claim of belonging. After thorough exploration, though, Lee came to the conclusion that “if you have to declare that you belong, then you don’t belong.”

It comes as no surprise that Lee is deeply influenced by Zen Buddhist practice. One of her initial encounters with Zen was on a trip to China to learn calligraphy. Instead, she became infatuated with the practice of “flung ink,” a catharsis of sorts in which Ch’an monks throw ink onto paper after a long meditation. This directly inspired No Up, No Down, I Am the Ten Thousand Things (1995/2000), an installation for which she plastered the walls of a white room with more than a thousand of her own “flung ink” paintings. These images, according to Lee, are “the exact embodiment of that moment in time, caused by the connection of everything that subtends the universe in that moment.”

In her more recent, primarily abstract artworks, Lee has taken great inspiration from this interconnectedness of the universe. Works like Secret World of a Starlight Ember (2020), an ellipsis of polished steel that has been pierced with thousands of tiny holes, encapsulates the absolutely expansive notion of the cosmic landscape. It illustrates the “net of Indra,” a Buddhist metaphor that conceptualizes the universe as a vast net of jewels, each one an individual yet simultaneously reflecting and containing every other. In Lee’s words, the cosmos is “the length, the depth, the breadth of everything has occurred, is occurring now, and will ever occur in the future, and we can’t extricate ourselves from [its] matrix … every individual life is the sum of everything that’s ever occurred to this moment, and stars somehow come into that.”

In fact, one of Lee’s two pieces shown at Appetite has a celestial theme: Reaching for the Moon in Water (2018). The print showcases a watery, monochrome, gray-and-black expanse with subtle details of tree branches, ripples, and small burn holes. These— along with the title— indicate to the viewer that this is an image of a reflection at nighttime, with the jagged shapes around the edges as mountains, the holes as stars, and the two dark circles as the heads of onlookers staring into the abyss. The artwork captures nature in a way that is reminiscent of a Zen garden: without being directly realistic or representational, it encapsulates the essence of a landscape on a small scale. The influence of Zen on Lee and her art is evident. The tree branch is done in the style of Sumi-e, traditional Buddhist landscape painting, and monochrome ink is a fundamental characteristic of Zen artistic practices. The use of Chinese ink, in particular, ties in the aforementioned “flung ink” paintings of Ch’an monks, as well as the traditional Chinese practice of calligraphy.

Lee’s second piece at Appetite, forgetting, remembering (2020-21) also utilizes Chinese ink, but features what are perhaps even more intriguing media: fire and rain. With them, Lee creates a vortex of abstract holes and spots. In true Zen Buddhist nature, she lets the forces of nature take charge, coalescing onto this sheet of paper. Of her process, Lee explains, “A lot of the work I make now, I leave in a rainforest, and the rain has been making these most delicious works for me … there’s just something joyous about actually admitting and surrendering to something that is bigger than your control… It’s a kind of meditation and being present to something as it expresses itself.” This painting utilizes environment as a mark-maker, a process that Lee is “fascinated” by. Forgetting, remembering is a visualization of the immense forces of nature, much like Chinese scholar rocks (or “gongshi”) which also serve to inspire Lee. These hole-ridden, unusual rocks— and Lee’s painting— are shaped and sculpted by natural forces across time, eventually becoming, in form and in symbolism, microcosms of the universe. As the titular word “remembering,” indicates, this artwork is a documentation of the world in a moment; only for us to “forget” all that is washed away by rain or consumed by fire.

James Jack

James Jack (b. 1979) is a contemporary artist based in Singapore who engages with land and the communities that live within it. He has created works for the Setouchi International Art Festival, Institute of Contemporary Art Singapore, and Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, and more. Jack completed a doctoral degree at Tokyo University of the Arts and then worked to establish the Global Art Practice MFA program there. In Singapore, his works have been exhibited at the Centre for Contemporary Art, the ADM Gallery at NTU as well as the Institute for Contemporary Art. He joined the faculty at Yale-NUS College as an Assistant Professor of Practice in the Visual Arts.

Much of Jack’s work utilizes soil samples as medium. The artist’s interest in soil stems from his own childhood experience of eating dirty vegetables from the garden, which he views as an innate desire to reconnect with the earth, the land from which we came and to which we will return.

The artist also draws from the history of landscape as a means to re-invision humanity’s relationship with the earth. Attracted to contemplative and meditative practices, James follows in an American tradition that includes Ralph Waldo Emerson, naturalist Henry David Thoreau, and the Hudson River School of landscape painting, among others. These traditions encompass different interpretations of landscape, some where nature is something to exploit, some where it is to be feared. In his own practice, Jack attempts to reconnect humanity with the land in a symbiotic relationship. His works are an homage to the land that nurtures us, the land we must remember to respect.

Another line of influence comes from Jack’s experience studying with a master calligrapher and painter in Japan. Jack deploys the gestural qualities of ink painting in his own work; for example, he created a series of landscapes and calligraphic compositions painted using hand-made pigments for his 2018 series, Œuvres à l’Encre. His method involved gathering butternuts and walnuts then separating the husks, grinding, boiling, and filtering the liquid to create handmade ink with which he then painted. The process is, as the artist describes, “meditation in action.” The works range from calligraphic compositions, to mountainscapes, to a tuft of grass on a blank page. When gathering natural materials from these specific sites in Japan, Singapore, Spain, the U.S. and other countries, Jack fostered close relationships with the people living in these lands. Besides drawing from his training in calligraphy, this series explores the social memories of place through intimate contact with people and their territories. This series also demonstrates Jack’s constant investigation of how to represent the land beyond the traditional media and subject matter of canonical landscape painting.

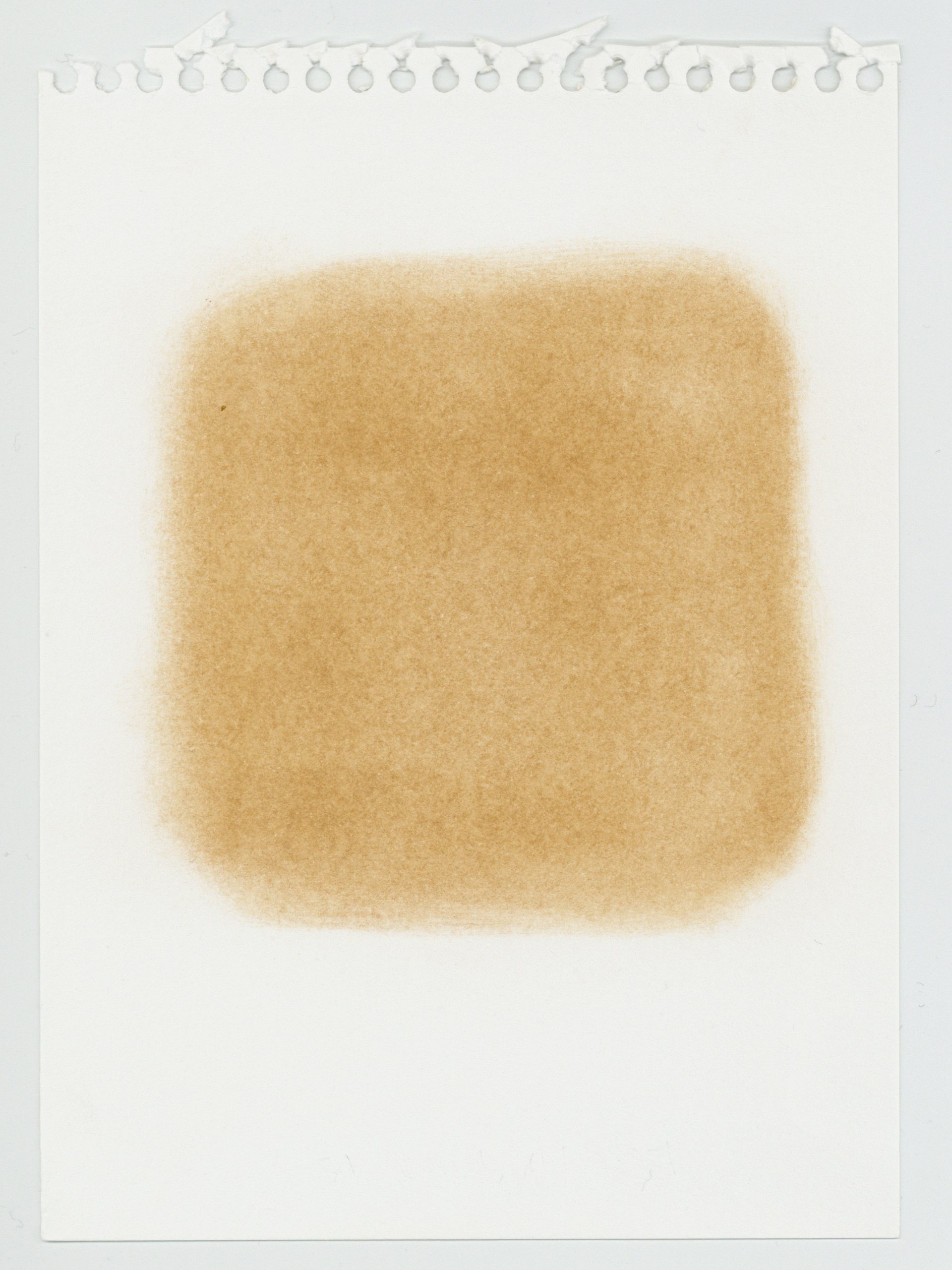

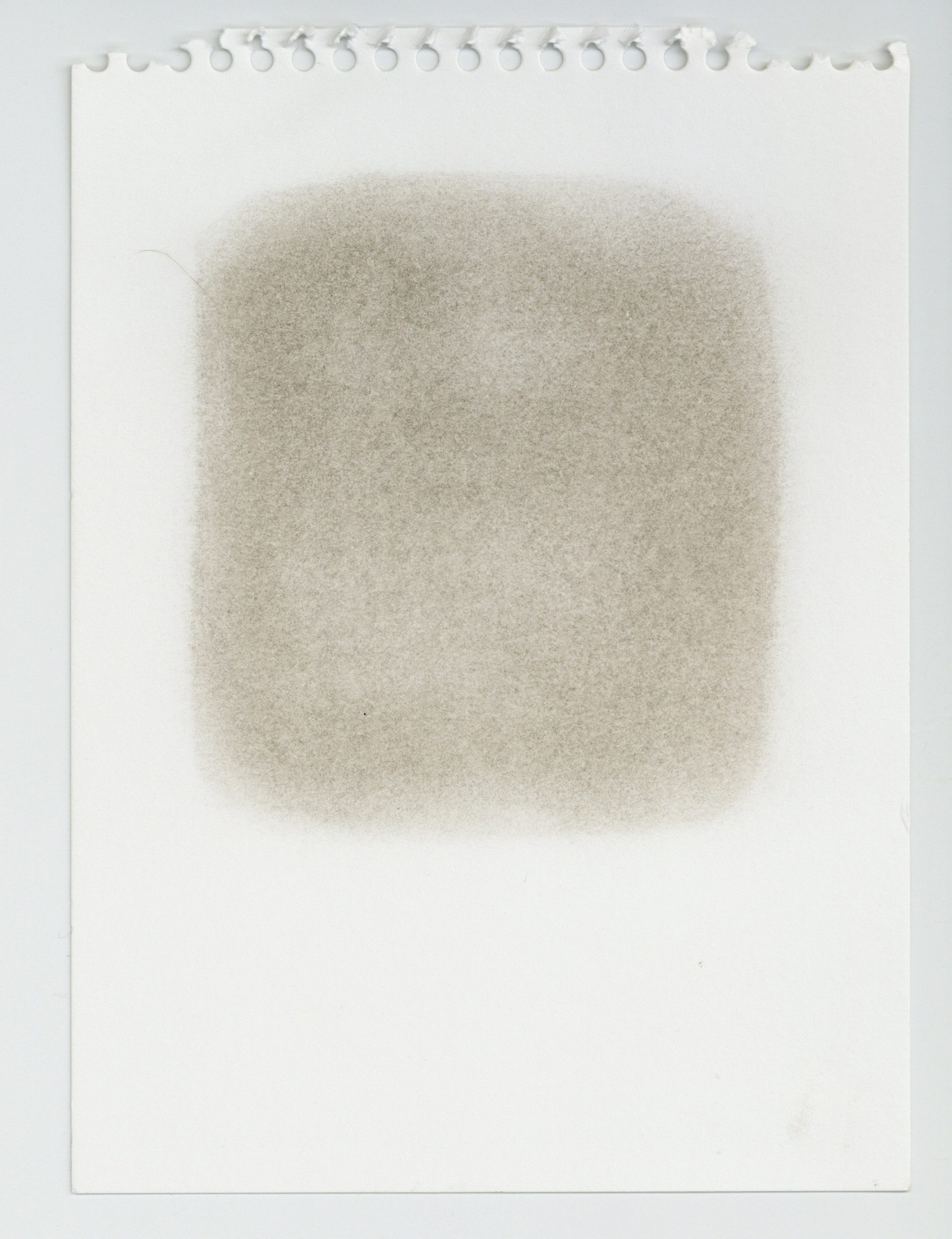

For the Iwaki Windows shown at Appetite, Jack was inspired by local oral histories and their connection to the earth. To make this series of pigment ‘rubbings,’ he utilized dirt from sites where these histories are embedded. As people shared stories about the land on which they stood, the artist borrowed samples of the soil (with permission from the community members), and rubbed them onto paper. He took samples from many regions, but perhaps most notably, from those affected by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown–mostly sites in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture. He even used topsoil that had been marked “toxic” due to radioactive fallout. These soft-edged squares can be seen as windows into the complex and often difficult histories that the soil holds within it. Appetite displays Jack’s Iwaki Windows pigment rubbings in part as a way to honor the 10th anniversary of the March 2011 (called “3.11”) disasters, which was this past March. By installing them in a seismic wave, the series formally alludes to the Great Tohoku earthquake. Jack has also taken samples from West Singapore to create Natura Naturata: Light of Singapore (2017). The artist invites the viewer to look through these transparent pigment samples and reflect on humanity’s relationship with the earth.

Sim Chi Yin

Sim Chi Yin (b. 1978) is a Singaporean artist and a 2017 Nobel Peace Prize photographer whose work integrates intimate storytelling with the social politics of landscapes. Her photography acts as a palimpsest of actions on territory, giving voices to the memories that have been silenced, contested, or hidden.

Her One Day We’ll Understand series (2018-ongoing) began as research on her grandfather’s experience during the Cold War, then expanded into a broader investigation on collective memory of the Malayan Emergency and the state imposed aphasia (the inability to find a language to speak about these histories rather than having completely forgotten them) that followed. The Malayan Emergency was a twelve-year conflict between the British colonial government and the resistance led by the Malayan leftists from 1948 to 1960. Sim’s grandfather was arrested in 1948, then subsequently deported by the British Colonial forces for suspect assistance to the Communist insurgency. By traveling to China, Hong Kong, Thailand, and Malaysia to interview and photograph people from her grandfather’s generation and the landscapes they remember, Sim Chi Yin reveals the layered memories hidden in the landscape. What contested narratives, trauma, and silenced histories does the land hold?

In Remnants #1, #11, #12, and #13 the artist intentionally photographs these landscapes out of focus, their blurred haziness symbolising the ambiguity surrounding the Malayan Emergency. By rendering the images obscure, Sim sets them apart from purely documentary photographs and instead imbues them with a kind of cerebral symbolism. Appetite includes four prints from One Day We’ll Understand . Remnants #1 shows a misty road in Betong, a town in southern Thailand where the Malayan leftists ambushed British security forces in June 1968. Remnants #11 shows Belum-Temenggor rainforest in Perak, Malaysia where the guerilla forces set up base during the Emergency. In this very rainforest, the British military constructed a massive man-made lake to flood the Communist forces out; Sim photographs this lake in Remnants #12 and #13. These images capture specific sites of conflict–places where key events of the Malayan Emergency unfolded. Infused into these lands is both violence and persistence, which Sim recovers and recounts through photography.

Sim’s dedication to social justice is rooted in her grandfather’s experience as a journalist and photographer before becoming involved in the leftist movement in Malaya. Much like him, Sim continues that same passion for political engagement in her contemporary photographic process; she gives voice to those who have been silenced.

In 2017, the Nobel Peace Prize commissioned Sim to create a solo show on nuclear landscapes using both video installation and photography. The show, “Fallout” opened in Oslo in December of that year. The artist travelled six thousand kilometers along the China-North Korea border and through six states in the United States to create this series of diptychs. The U.S. was the first country to have ever tested and used nuclear weapons, while North Korea is the only country to have tested them in the 21st century. These two countries are locked in a dangerous cycle of threats and counter-threats. Sim’s photographs of testing sites, storage silos for missiles, nuclear factories, and more reflect humanity’s relationship with these lethal weapons–both past and present.

Apart from her Nobel Peace Prize commission, Sim has exhibited in the Istanbul Biennale (2017), the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art in South Korea, among other international institutions. She has been twice nominated for the Prix Pictet, and won the Chris Hondros Award in 2018. She joined Magnum Photos as a nominee member in 2018 and is currently also a doctoral researcher on scholarship at King’s College London.

Yang Yongliang

New York- and Shanghai-based contemporary artist Yang Yongliang (b. 1980, Shanghai) fuses the iconography of the present with traditional aesthetics. Schooled from a young age in traditional Chinese calligraphy and painting and educated at the China Academy of Art, Yongliang harnesses his deep familiarity with the conventions of shan shui (‘mountains and water’) painting in order to grapple with contemporary questions of globalization and urbanization. His works are included in permanent collections at institutions such as the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Contemporary Art Center of Thessaloniki. Some of his recent solo exhibitions include Artificial Wonderland, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, New Zealand (2019), Journey to the Dark, Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney (2018), and Time Immemorial, Galerie Paris-Beijing, Paris (2017).

Yongliang’s compositions have their origins in traditional Chinese shan shui paintings—a style characterized by idealized, harmonious depictions of natural landscapes. Rather than a focus on realistic representation of scenery, the aim of a shan shui painting is to express the mystical effect of the natural world upon the artist. This practice also involves strict guidelines which a painting must follow: each scene must contain a ‘path’, ‘threshold’, and ‘heart’, and must adhere to principles of Chinese elemental theory with regards to color choice and mixing. As a result, the style is deeply symbolic in form and structure, with ties to Taoist ideas of harmonious existence with the natural environment. Yongliang’s work, at first glance, offers a monochromatic yet seemingly tranquil natural scene— only after close inspection are the grim cityscapes revealed.

The imagery of Yongliang’s hyper-urbanized scenes find their origins in Shanghai, the artist’s hometown. As a lifelong resident, he has witnessed Shanghai’s unchecked, metastatic growth completely alter the cityscape within the artist’s lifetime; in response, he subverts the romantic forms of shan shui as a mode of nimble critique. Each piece is a composite of thousands of Yongliang’s own photographs of Shanghai, meticulously arranged so that a hill encrusted with high rise buildings and power lines morphs into a mountain blanketed with trees; meandering mountain pathways are replaced with the arrow-straight lines of highways boring their way into the mountains. For Yongliang, the photographic aspect of each work is key, with the images acting as captured moments of time that are then assembled into fantastical yet disconcertingly familiar urban scenes.

Yang’s 2017 video, Prevailing Winds, is a seven-minute long 4K film of a digital shanshui. The work depicts the free-flowing dynamism of a waterfall existing in strange disjunction with city traffic and urban decay. The scene remains still except for cars, the surrounding waters that ripple in the wind, and the waterfall pouring down the mountain. At the beginning of the film, these moving parts are quite subtle. By the 6-minute mark, however, the scene speeds up like a time-lapse, and a sense of impending doom takes over. Just as the film seems to be coming to some sort of climax, the screen fades to a white with the work’s title; the clip ends. Prevailing Winds is full of examples of discordance that unsettle the viewer and provoke one to critically engage with this urbanized reality. By creating a mountainscape from composite images of quotidian city infrastructure, Yang closes the gap between the urban and the natural, conveying the idea that the two have become inextricably linked, that the effects of environmental destruction can be felt in urban centers as well. Yang foreshadows what our world may become if urbanscapes continue their rampant growth with little to no concern for the environment that is being destroyed in the process.

The Streams (2016) and Sinking (2016) also feature the most ubiquitous elements of city life: power lines, colossal motorways, rusty sheet metal, and crumbled asphalt. Industrial debris covertly fills out shanshui outlines, creating an uncanny harmony that elicits a second glance. Alongside considerations of environmental degradation and rampant globalization, Yongliang’s contemporary landscapes draw attention to the hyper-urbanized spaces we build and inhabit—and the likeness they share with organic worlds that can often seem fantastically remote. These images prompt us to ask: why might it matter that our city spaces can be so easily mistaken for naturalistic forms? What might this similarity say about a collective longing for something like the harmony expressed in shan shui paintings?

With the generous support of:

Sullivan+Strumpf Gallery

Hanart TZ Gallery

Sundaram Tagore

National Arts Council (NAC)