A TOUCH OF A GAZE:

I DON’T KNOW WHAT I AM SEEING; BUT I KNOW THEY ARE SEEING ME

by Yanyun Chen, presented on occasion of STAGING: MAPPLETHORPE on 29 May 2022.

To begin, let us close our eyes and feel our skin.

How it incrementally ripples and fuzzes as one inhales, the breath held, hair standing, our nerve endings under our skin, pores perk up in waves of gentle tides filled with warm sensations. We taste at the tip of our tongue the back of our lips. Then breath escapes, leaving a trace of pressure under our nose. Here comes the echoes of our throbbing heart. We pay attention, the motion repeats with subtle changes, our heart responds to the pace of our lungs. Or is it the other way round, pumping ahead at different rhythms.

French philosopher Jean Luc Nancy thinks of the skin as a boundary between two outside worlds: outside, the one which surrounds us in an environment and pushes us about, and outside, the one inside us which we can only assume works and moves us: blood, veins, organs, bones, muscles, a sea of red. Pressure is felt from the inside pushing out, and the outside pushing in, and the tides of touch on skin forms the shapes which we occupy and which occupies us.

To verify that the world outside is within our skin, we embrace the knife and a witness to be our eyes. We trust the eye of the other to tell what we are made of. A photograph is sometimes this other that we rely on. In the realm of the eyes wide shut, what can we see of a machine that has seen for us? What do we see swimming in the sporadic darkness of the back of our eyelids?

What do we know of landscapes and hills of our skin?

Our fingertips encounter a sensation, it’s resting on something soft. Perhaps, something hard. Or velvety, or rough. It carries a temperature that tells us relative things like “cold” or “hot”. Perhaps, it is something familiar, or surreal. “Never thought this would feel like that,” we might think. Can we feel colour? Can our finger-tips see every edge, line, shade, and raid the vision of our eyes? Can we touch a photograph?

Eyes open. Staring back at us. Can we see our own faces without a mirrored gaze? Without the intermediary silver, without a witness to stare back at us, for us to trust? Do we trust our eyes? Who do we trust as our eyes?

Robert Mapplethorpe

Tulips, 1979

Silver gelatin print

50.8 x 40.6 cm

Courtesy and © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Our bodies are a tracing of two worlds, a sketch that is constantly in the making. Every ray of sun marks a line on the shade of my skin, every cool breeze crackles a pore, every brush dead skin disperses, new skin arrives. Every sip, every morsel of food pushes through our oesophagus, pushes us out to occupy space, feeding our silhouette from the inside out. Cells renew, and blossom to the surface. The cells on the surface of our skin are dead, “protecting the soft centres from the intrusions of the outside world.” We are mammals with zombie skin, constantly shedding in abandon.

We hug.

“The dead you is constantly being rubbed away by the dead me. Your cells fall and flake away, fodder to dust mites and bed bugs. Your droppings support colonies of life that graze on skin and hair no longer wanted. You don’t feel a thing. How could you? All your sensation comes from deeper down, the live places where the dermis is renewing itself, making another armadillo layer. You are a knight in shining armour.” (Winterson, 123)

“Written on the body is a secret code only visible in certain lights; the accumulations of a lifetime gather there. In places the palimpsest is so heavily worked that the letters feel like braille. I like to keep my body rolled up away from prying eyes. Never unfold too much, tell the whole story.” (Winterson, 89)

Like braille—the writings of and on our skin pressed by the passage of time from both outsides. A language that requires a lover’s patient reading, a secret code unbeknownst to us in areas our necks cannot twist our faces to see. Perhaps, the Japanese mythical spectre Rokurokubi, the long neck woman whose head floats beyond her bedroom doors at night, her soul on an adventure, searching for love, searching for terror. She would be able to see herself in the dark areas out of sight. Yet even then, would she be able to read in the same way her lover does to her, for her, of her? I’d like to think that ghosts and spectres have lovers too.

Do we have witnesses in the room?

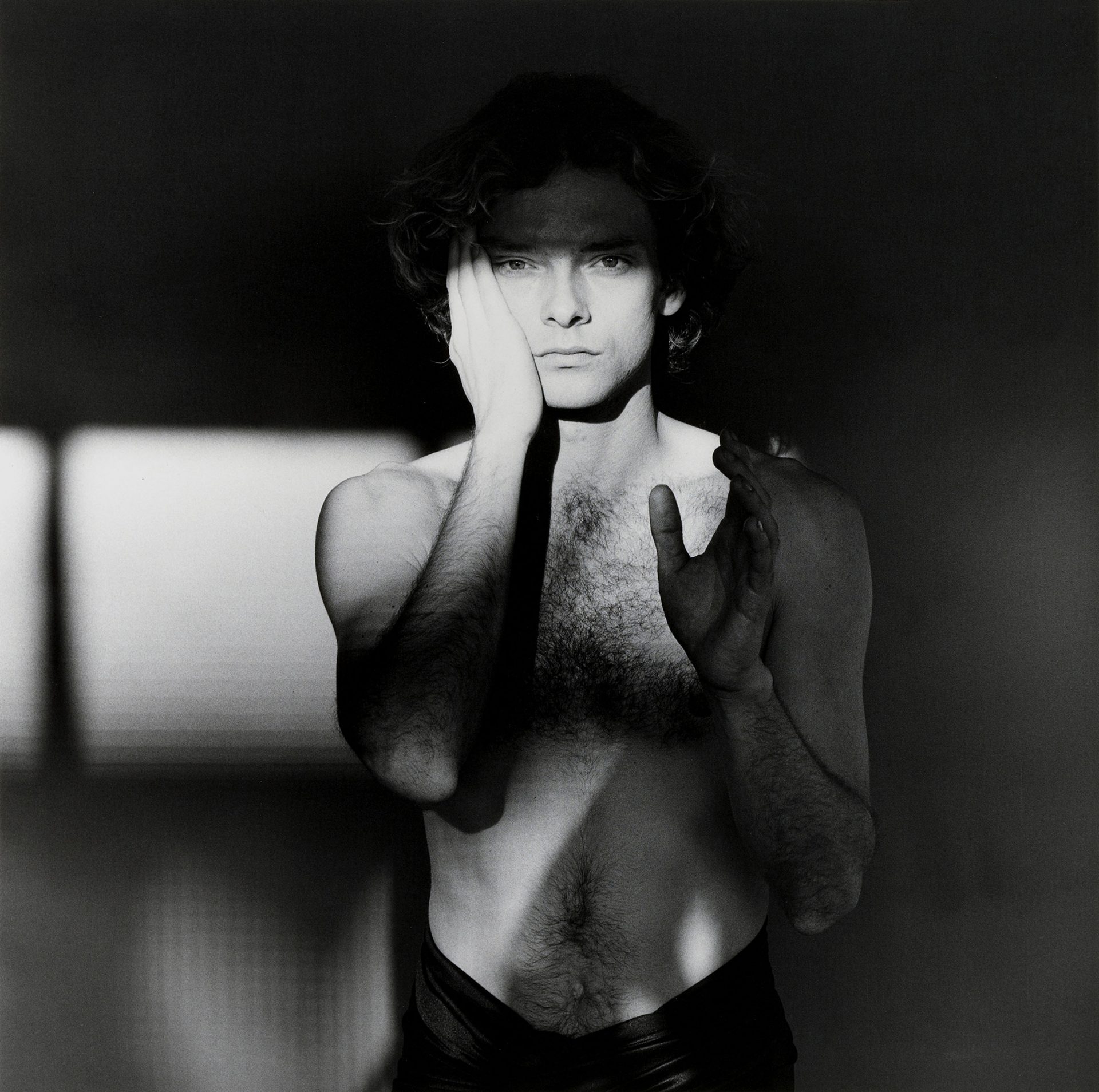

Robert Mapplethorpe

Alan Lynes, 1979

Silver gelatin print

50.8 x 40.6 cm

Courtesy and © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Alan Lynes is a ghost with a lover. The shaded touch of a half-gaze, softly frozen melting glass, slow moving arctic ice, infinitely warm. The curls of hair tickled by air and shadow, intricately traversing across the chest, down the navel, into the depths of a plunging wrap across the waist. The curls on Alan’s crown wavers. His gaze falls upon us gazing at him. Our eyes do not meet. He, this image unmoving, knows and quivers at the corner of our eyes just as we forget to see him, as he has forgotten to see us.

“What the Photograph reproduces to infinity has occurred only once: the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially.” Once, then, and now forever. It is the Particular. This photograph, and not Photography. “Look” “See” “Here it is”; it points the finger at a certain vis-à-vis. It always is a specific photograph.

This specific photograph has met this specific photographer. A touching of skin on skin and gaze on gaze: Alan met Robert. And between the air where the touch of sight was encountered, a look hovers, suspenseful, suspended. A ghost is captured in the machine, the Dorian Gray of hazy memory, beauty frozen while the body withers. A ghost who haunts the hallways staring back gently, now and forever.

“In the beginning, there is Chaos: the first of all the gods to be born from nothingness, and the only one to remain after they have all disappeared. After it, Gaia, with her vast bosom, appeared, and so did Eros. Chaos, Gaia, and Eros are the knot from which the history of the world and the mortals who inhabit it develop.”(Nancy, 55)

“The photographer has found the right moment, the Kairos of desire.” (Barthes, 59)

Robert Mapplethorpe

African Daisy, 1982

Silver gelatin print

50.8 x 40.6 cm

Courtesy and © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

A splash. Suspended animation. The Rokurokubi’s neck raises high, her elegant stem, her white long throat, her pearly skin shimmers as her body rebounds from the wet sculpted mirror. Silver in suspense, grown from the night. She passes Alan Lynes by, two ghosts at home in their haunt, old friends who understand the poise of a gaze, eyeslashes aflutter, half shaded, in desire.

Roland Barthes once echoed Franz Kafka, “We photograph things in order to drive them out of our minds. My stories are a way of shutting my eyes.” (Barthes, 53) What drove the African Daisy to the sky, surrounded by shadows of the night? What does she hope to see as she floats above the sleeping bodies of dreamers, lost wanderers?

Yet the photographs are watching us as we sleep. They cannot drive anything out of their minds, for they are held hostage, arrested in their stillness, as the light wears off the ink of their skin, lightening not darkening the pores of the print. They age as we age.

“In this glum desert, suddenly a specific photograph reaches me; it animates me, and I animate it. So that is how I must name the attraction which makes it exist: an animation. The photograph itself is in no way animate (I do not believe in “lifelike” photographs), but it animates me: this is what creates every adventure.” (Barthes, 20)

Alan Lynes and the African Daisy are on an adventure, they take flight.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Flower, 1980

Silver gelatin print

50.8 x 40.6 cm

Courtesy and © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

I am animated. The small circular pore, the perfect dent, the inconspicuous nipple almost out of frame, floating in nothing but an overblown, overexposed whiteness. This nipple of an inanimate furniture shudders me like the shadow play on the wall. I suppose this is what Roland Barthes notates as the punctum: “it is what I add to the photograph and what is nonetheless already there”.

The playful bush, sparse yet distinct, runs across the chest of the image. The tilt of the neck of flowers, the touch of bristle on stem, the lean. The shapely, tubular pants contain the flourish of stoic blooms. The dance of lines in the far corner. The resolute nipple of a cabinet.

“Philosophy is an art of touching, just as sex is an art of intelligence.” (Dufourmantelle, 9)

“… but none emerges unaffected from a confrontation with desire.” (Dufourmantelle, 6)

When desire plays on the surface of images, and teases us with charm, we long to touch these imperfections, from smooth to rough to particular. French psychoanalyst Anne Dufourmantelle reminds us that philosophy and sex are both acts, and both are obsessions

“There is no true thought that is not obsessional, that does not turn endlessly around the same question, that does not return again and again to the modalities of an unformulated question. An obsession that operates in the shade, shaping every life, every thought, every work, because what is ultimately at stake is the same desire. Sex, love, philosophy.”

“For it is not indifference which erases the weight of an image… but love, extreme love.” (Barthes, 12) A love that is arrested in its rupture, for the image is still, still waiting.

“When I say ‘I will be true to you’ I am drawing a quiet space beyond the reach of other desires. No-one can legislate love; it cannot be given orders or cajoled into service. Love belongs to itself, deaf to pleading and unmoved by violence. Love is not something you can negotiate. Love is the one thing stronger than desire and the only proper reason to resist temptation.” (Winterson, 78)

I’d like to think that Mapplethorpe fell in love, he fell in love with Alan Lynes and the African Daisy. He fell in love with the cabinet. In his love, he stole an image from the ones he loved, and made them ghosts who haunt his corridors long after he is gone. It is a kind of immortality, perhaps, of saving the moments too quickly gone.

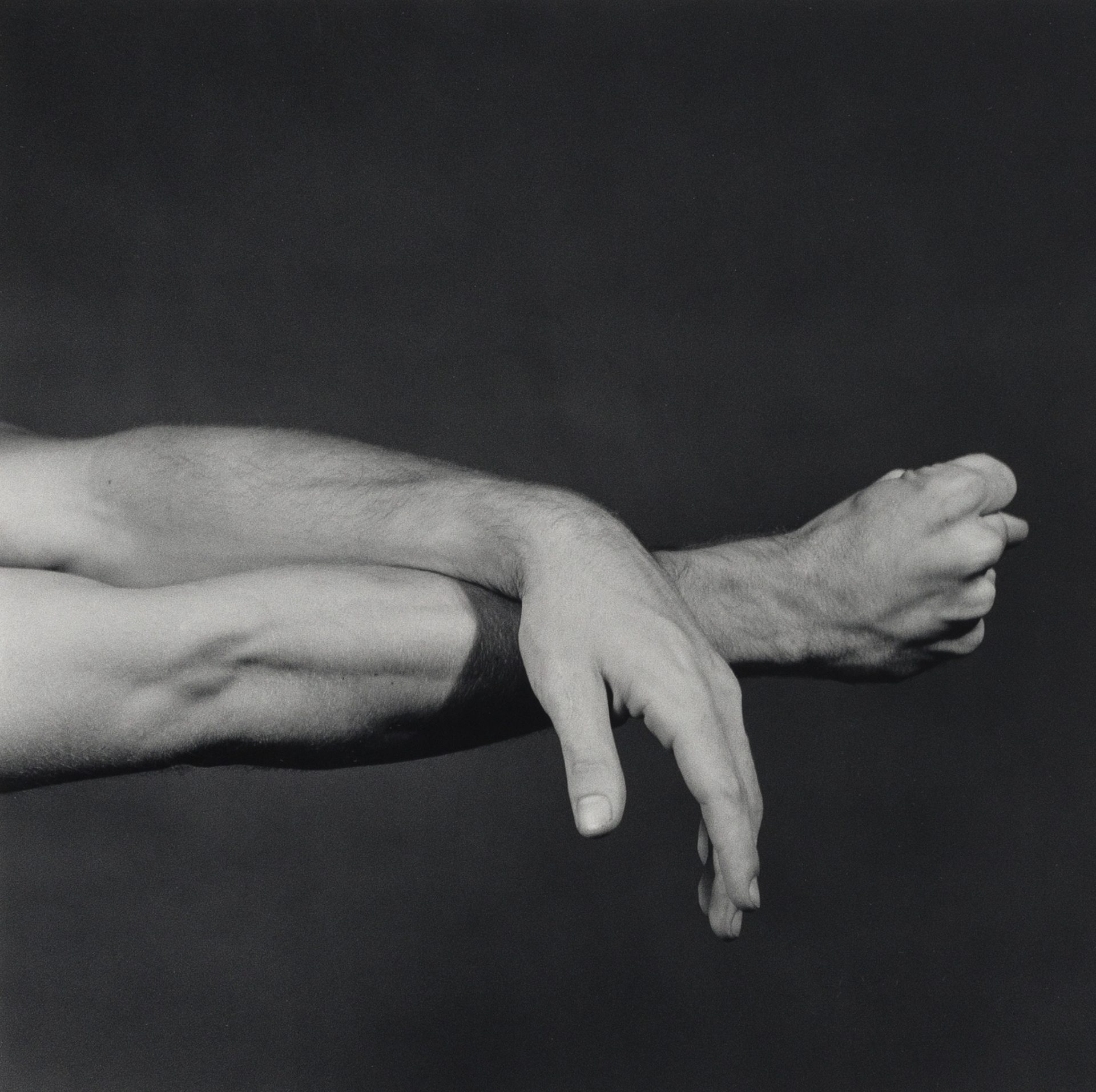

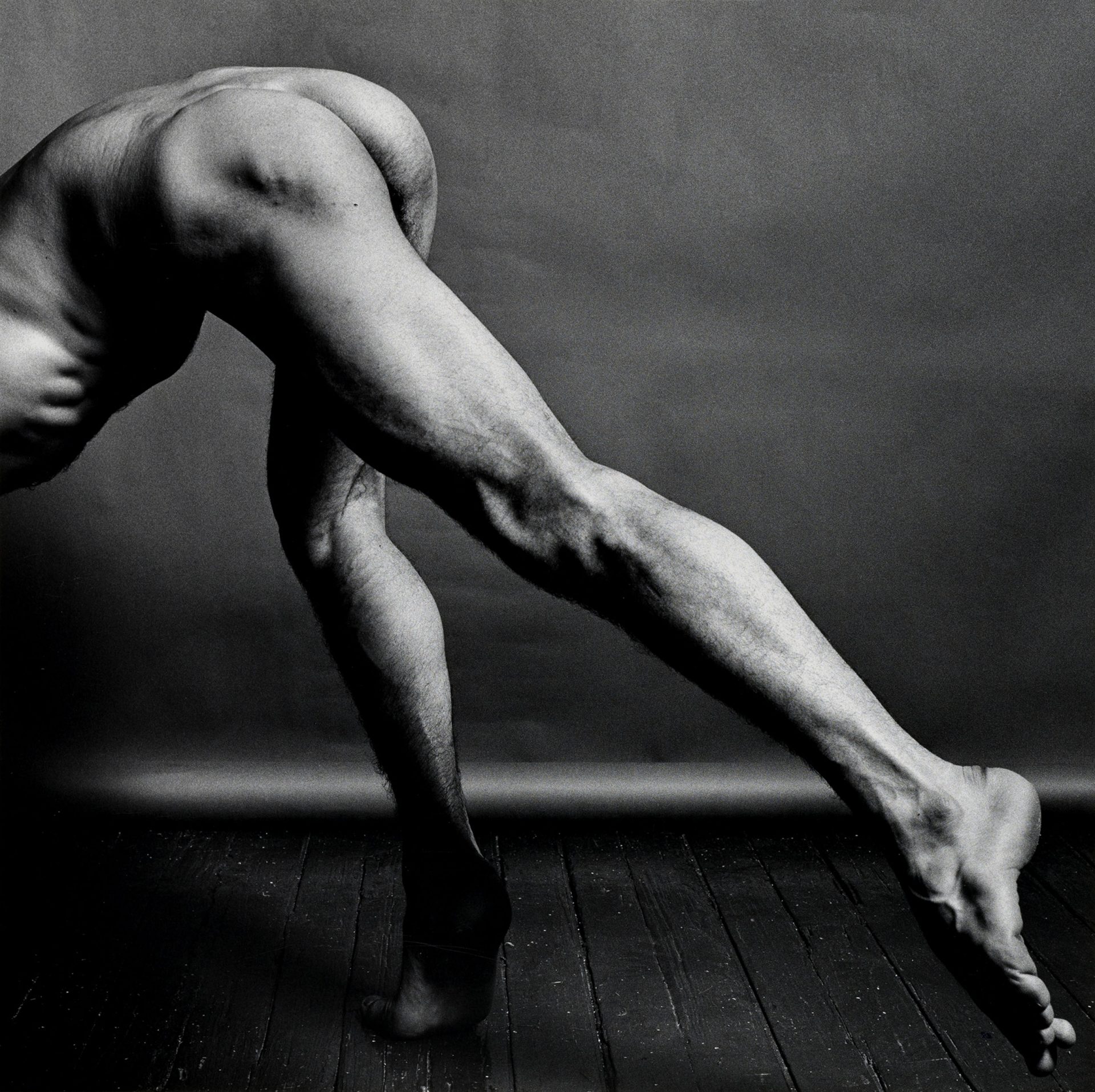

Robert Mapplethorpe

NYC Contemporary Ballet, 1980

Silver gelatin print

35.4 x 35.1 cm

Courtesy and © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

“In front of the lens, I am at the same time: the one I think I am, the one I want others to think I am, the one the photographer thinks I am, and the one he makes use of to exhibit his art.” (Barthes, 13)

Who do we want to be in front of a lens, to be remembered as an image? What poise, what posture, how do we want to be captured? Power, repose, force, limp, dominant, submissive.

Velvet Underground “Venus in Furs”

Venus in Furs is written by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, from his name came the term masochism, defining it as “sexual gratification from one’s own humiliation and pain.” He comes from Lemberg, Galicia, (today known as Lviv, Ukraine). This book was first published in 1870. Von Sacher-Masoch was obsessed with the subject of domination and submission, himself entering a contract to be the slave of his mistress Fanny Pistor, inspiring the writing of this text. In the interplay of power-humiliation-desire, two characters enter into a contractual agreement of slavery and mistress, Severin von Kusiemski and Wanda von Dunajew.

‘What an idea!’ I cried. ‘You fill me with horror.’

‘Do you love me any the less?’

‘On the contrary.’

On the contrary. Where fear itself is the power, where within the restful flaccidity lies the potential for tension and drama, for the possibility of the next moment where the limp soft fingers arrest themselves into a ball of fight. Clench and release, the motors of passion pumping through performance. Perhaps, the photograph isn’t held hostage, but holding its breath, waiting for the rupture of release, a forgetting that comes without reason. An exorcism. Or are we held hostage in our awe for the image? Who will be forgotten first? For is it not, that forgetting cannot be controlled, intended, called to presence? Forgetting happens to us.

How would one like to be remembered?

How would one like to be forgotten?

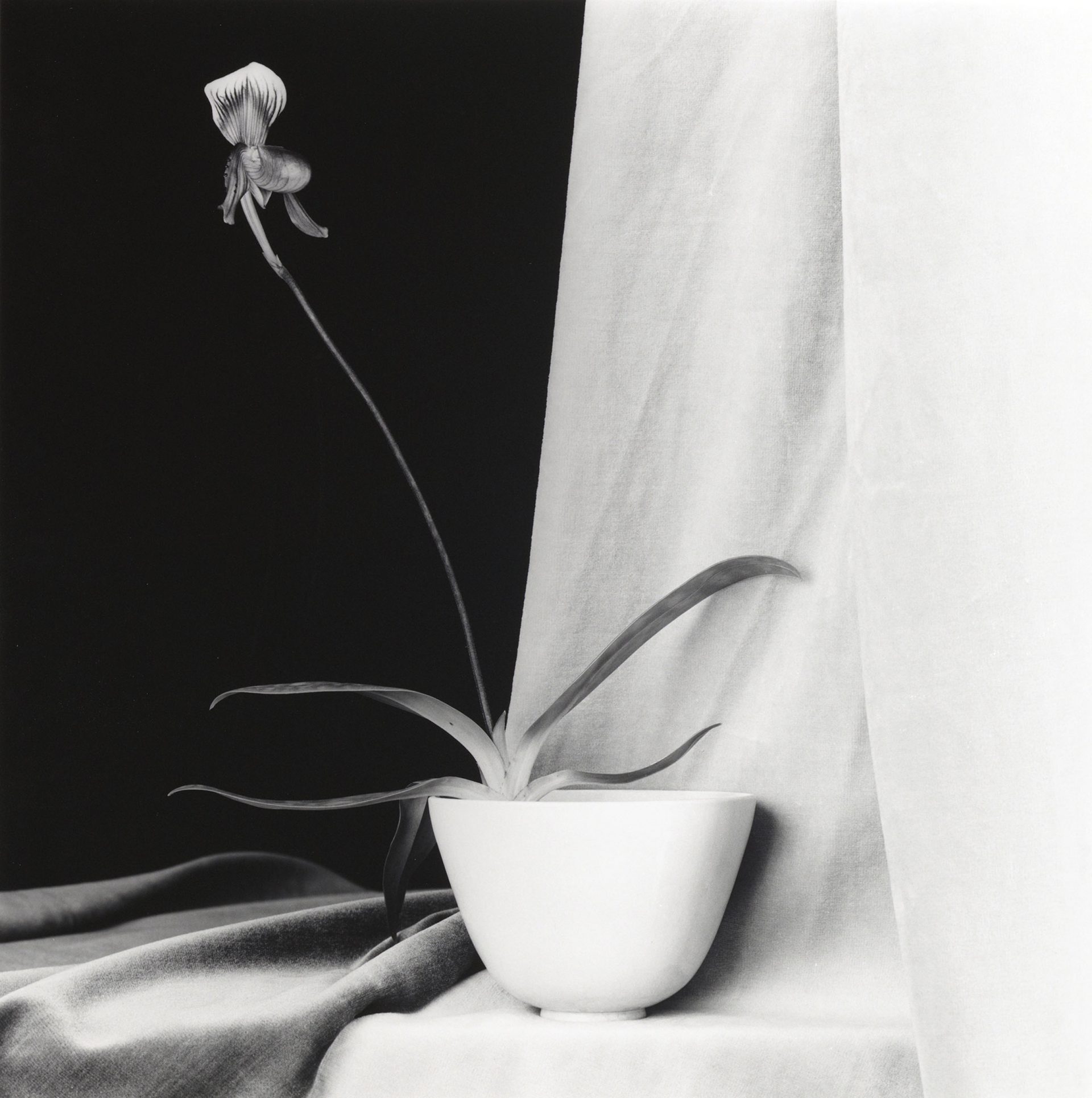

Robert Mapplethorpe

Orchid, 1986

Silver gelatin print

61 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy and © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

The withering tulip rests its tired neck on the erect stem. The ghosts are taking a break from staring back from a different realm in shared spaces: us, them, divided by sight. The long languid neck leaning towards the darkness. There is something sensual about the undulating leaves, different characters reaching out, touching the draperies gently. Flutter, aflutter. On standby.

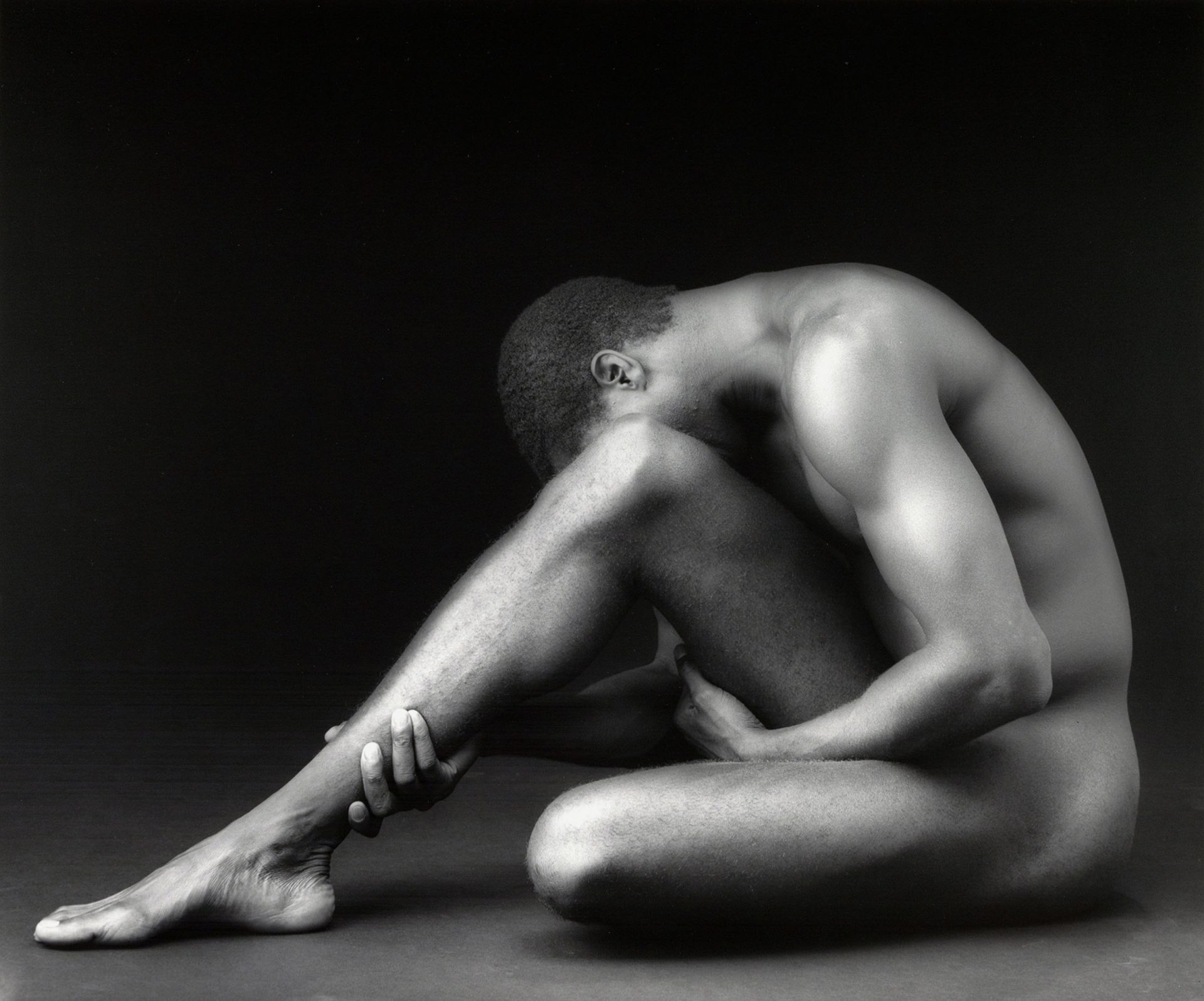

Robert Mapplethorpe

Phillip, 1979

Silver gelatin print

50.8 x 40.6 cm

Courtesy and © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

The nude is a presence above all, a presence exposed to the gaze of others. A nude, any nude, always finds itself being looked at, even when I am the only one looking. The gaze, when it encounters the nudity of the body, attests to its presence. The naked body is present in the gaze. And its presence is indubitable: it is there.

But the presence of a body is also always fleeing the gaze that makes an image of it. When the body is made into an image, it leaves itself, exceeds itself. A body is never given as definitively present to itself or to others, even though it is also not pure absence. The vision of the naked body is exactly the experience of this presence that always flees into absence, into the impossibility of being an immobile given. My body is never given.

All true photography of the body is always at the same time the anticipation of the gaze and the projection of the subject outside of itself. (Nancy, 75)

Robert Mapplethorpe

Tiger Lily, 1987

Silver gelatin print

61 x 50.8cm

Courtesy and © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Robert Mapplethorpe

Tulips, 1979

Silver gelatin print

50.8 x 40.6 cm

Courtesy and © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Bodies. The long neck, the solid trunk, the round hold, the translucent structures like corsets which bind, erect and prop into position. Like pillars and plinths, columns, towers and chimneys, it occupies space, it supports our heads to the sun. Yet it is the soft luminescence of the body, the sharp angles and deep curvature, the solidity which allows for a frivolous turn of the head, the scandalous pollen of the anther to fertilise the ovary, the self-production of fruit and seed. Powder puffs of sex falling on trembling petal while the body holds their floral chins up high. It drags up hydration and produces sap, it rots as it drinks, withering from bottom up, its roots long gone as it awaits for death.

We lift the glass to our lips, and taste blooms on our tongues. One must thank the resolute stem for standing still in order for the flavours of thought, beauty, and light to shine within the shadows of our mouth.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Tyrone, 1987

Silver gelatin print

61 x 50.8 cm

Courtesy and © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

And so we remain, eyes wide shut, staring yet not quite seeing the image before us. We consume with our eyes, with our mouths, with our noses. Yet, what can be known in the process? I confess: I don’t know what I am seeing.

Meanwhile, the photographs are listening to the thump of our hearts which has escaped the confines of our bodies. The beats echo through our organs and land out on the wooden floor, bouncing off lamps and long shadows, and the shimmers of glass and brass and steel. The photographs move us. It animates us. It puppets us into being.

The ghosts are watching.