Thai contemporary artist Pinaree Sanpitak (b. 1961, Bangkok) is one of the most highly acclaimed artists of her generation, best known for her practice centred on the female body and its forms. Since her photographic collages of the early 1990s, Sanpitak has consistently reworked and reshaped the breast-stupa— a commonly recurring motif in her work— with a diverse range of materials. Examples include Noon-nom (2001-2002), an interactive installation featuring breast-shaped pillows, and Breast Stupa Cookery (2005-present), an ongoing collaborative project where Sanpitak invites chefs to create meals using breast-stupa-shaped cooking molds.

Sanpitak regards the breast-stupa as autobiographical, drawing upon her identities as a woman and a mother. Notably, however, Sanpitak also directs our attention toward the universality of the shape.

At first glance, it might seem difficult to detach the breast-stupa from its associations to Thai Buddhist culture and the female body. How might we find other ways to relate to Sanpitak’s artworks? What else can we find that would resonate with our own experiences?

The domical form, both in Sanpitak’s works and as an architectural structure, has housed a wide range of meanings: from overturned alms-bowls to vessels, to memorial mounds and heavenly dwellings. Sanpitak’s works, in their simple yet distinct forms, take on some of these connotations to create atmospheres that invite contemplation and reflection.

Throughout her career, Sanpitak has pushed the boundaries of form, material, and participation. At Appetite, we expand the ways in which her works can be experienced and received— not in a white cube gallery, but a relational and multi-disciplinary space.

Yanyun Chen (b. 1986) is an emerging visual artist based in Singapore who runs a diverse practice. While her foundations are grounded in classical drawing and animation, Chen has also produced a number of notable installation projects, such as The scars that write us, which was awarded the People’s Choice Award at the 2018 Singapore Art Museum President’s Young Talents Exhibition. This project, as well as her subsequent solo exhibition Stories of a woman and her dowry (2019), takes on an auto-fictional lens to examine the female body and its inheritances, in particular the ties that bind a woman to her family.

Hills Like White Elephants anticipates Chen’s artistic shift towards the female body and its experiences. At the same time, this triptych is also an excellent representation of her charcoal-based drawing practice, which inquires and subverts techniques and traditions of academic art forms. Charcoal has been historically considered by Western artists as the medium of unfinished work. By using charcoal to create intricate compositions reminiscent of the 17th-century Dutch still-life tradition, Chen challenges conventional perceptions of charcoal while simultaneously showcasing her mastery of the delicate medium.

Chen embraces these complexities with precision and provocation, offering personal answers and universal questions. What do we do with the cultures, stories, and expectations that we learn and inherit? How do we negotiate our place between the past and the future?

In Conversation with Yanyun Chen

Kathy: I’d like to begin by sharing a bit about why we wanted to present Hills Like White Elephants as part of the She/Her exhibition. We were drawn to your interest in the female body, its forms and experiences. This has been a recurring subject for you, especially within the past two years with projects such as your solo exhibition Stories of a Woman and her Dowry, and the short film Women in Rage, which very recently won Best Animation at the Q3 Prague International Indie Film Festival. Hills Like White Elephants predates both of these projects. We were particularly interested in this series, because apart from its subject – which you’ve explained as a reflection on feminine personhood – there is also an element of how this work is, in a way, cross-cultural. Visually, we have the metaphor of the flower vase, whose Mandarin term 花瓶 also has connotations of a “woman-on-display” (essentially suggesting that this woman only serves to provide visual pleasure). On a literary level, the title of this work refers to a short story by Ernest Hemingway, which centres on a conversation that is implicitly about abortion. I’m wondering if we could talk about the significance of the Hills Like White Elephants triptych to you. What drew you towards creating a visual response to Hemingway’s short story?

Yanyun: So the work wasn’t actually done in response to the Hemingway story. I was thinking a lot about the notion of the 花瓶 – the flower vase, and I’ve always wanted to do a work with that very classic blue and white china, or porcelain, either from the Netherlands or from China, because I just always liked that visual. It just so happened that there was a porcelain factory in Singapore that was closing down. I made a trip to go and see all these pots and bowls and it was just the kind of visual that I was looking for. And since they were selling it for cheap I just bought a whole bunch.

When the opportunity came for me to do a sort of still-life set-up, I arranged it, and I knew in my head I wanted to do a triptych. I have this habit when I draw, which is, when I’m close to say about seventy percent done, I actually turn the entire drawing upside down to check the work’s visual balance. With this work, when I did that, I paused, and couldn’t see it any other way. And I thought I was doomed! Because I did not plan for this, you know.

One of my friends- Jeremy Fernando- saw the work upside down and asked if I had read Hills Like White Elephants. I think the lines clicked together right after that. It’s been a while since I read the short story, but I always remember its textures. In the middle of the conversation at some strange moment, the female protagonist turns away and says “those hills look like white elephants.” And that’s all she says, but the pregnancy of that phrase sort of glued itself to the visuals— the suspended conversation; the suspended possibilities. Things that are very fragile and very important, are still. The world is there. And so all these sensations made this work.

Kathy: I think our approach to reading your work was very different from the process that you just described, because we saw the title and assumed that the story preceded the drawing.

Yanyun: It was a connection that happened by accident, that came while I was doing the work and trying to figure out what I was doing. I think there is something very beautiful in those moments when you thought you were going one way, something just veers you off course, but actually gets you closer to what you’re trying to do.

Kaushik: I’m interested in the associations in your work— porcelain and the fragile woman on display, voluptuous figures, but at the same time there is an undeniable strength and empowerment to the work. How do you see this tension between being read as both feminist and anti-feminist?

Yanyun: You could definitely say that I am perpetuating certain tropes. I’m borrowing from the notion of the vase, the female vase, and I am perpetuating it. But I cannot run away from something that is just right there, especially since I am responding to, drawing from, and speaking about it. But at the same time I think of that moment of suspense, visually how these porcelain objects are hung in the air, suspended, which changes our associations with the trope of the female vase.

And the fact that, yeah I cannot control who sees the work and how they see, and the kinds of baggage that comes with their visual experience, right? Because when I displayed the work previously in a show, we got all kinds of comments and I always enjoy listening to what people think. You have the ones who appreciate it a lot because it’s so classical – they love the fact that it is so classical, and then it makes them extremely uncomfortable with the fact that the porcelain is upside down. And then there are the ones who get the contemporary links but really don’t like classical drawings. Because they feel that it is perpetuating some kind of tradition, or approach. But it opens up people’s assumptions. A lot of people were like, “Why did you make it into a triptych? Why did you divide it into three, but not evenly and it’s kind of a reductive scale, at the same height but it gets narrower and narrower as you go?” And the biggest part has the most white spaces. To be honest I have no answer for that, it just naturally evolved and it had to come this way. There is also discussions on the significance of porcelain objects, this particular kind, the Dutch blue and white porcelain, and the conflicts in history with Chinese porcelain. Who came first in this aesthetic? Who did/does it better? It’s kind of a perpetual kind of debate if you read up on porcelain. These objects that I have, they’re not the refined stuff. They were made from a Singapore porcelain factory, you know. They’re not special, actually, they’re uneven and very wonky. So there are all these connections that come to an object like this that are very fascinating to play with.

Kathy: This next question came out of thinking about your visual metaphor of the woman on display, because I thought that it was interesting how by using charcoal to depict porcelain, it’s like rendering it as a two-dimensional object, and in this way the porcelain themselves also lose any practical purpose, and yet they’re also on display. I know that charcoal is a medium that you’ve worked a lot with, but I also noticed that in a number of other works you’ve also worked with different mediums, or had still-life drawings of flowers and an actual installation piece in front of it. So I was curious about how you decided on the medium for this work. Why did you decide to use charcoal?

Yanyun: Well, charcoal is a medium I’ve always been using that I’m very familiar with and like it a lot. I do remember when I first started the flower series the thought that I had was, “Ok, these Flemish paintings of flowers: it’s just one of these iconic images that when someone mentions the term, you can recall an impression of it. But, it’s always in colour.” So when I was trying to figure out what to draw I thought about it and went, “I’ve never seen it in black and white.” So I just tried, and the flower series grew from this familiar trope, just in an unnatural medium.

Same with the porcelain blue: we’re very familiar with the blue that comes with this kind of porcelain. And I just mentioned in there, everyone has their own concept of blue. It doesn’t have to be the exact blue, but it’s that blue on white. When you reduce the saturation, people still cannot see it as black and white. They recognize it as that kind of blue, on that kind of white, and that kind of vase. There’s a bit of fun for me to find something that’s very familiar, familiar to the point that you take it for granted that you actually know really well, and then use a medium that I enjoy very much to see what happens to the assumptions that we have in our head. Because, what if I told you that the patterns were not blue? What if I told you it was that red kind of, Chinese porcelain red that was patterned? It throws people off. Because they’ll ask, what do you mean it’s red? So it is a certain kind of assumption.

And I like these kinds of moments in making works which are just a bit off. It was an active choice to use charcoal. I knew quite early on that I wanted to do a piece that involved these kinds of porcelain pieces in charcoal, with a very white background. I wanted to see how far I can push an object that’s arriving, but also kind of disappearing. It’s a technique that I have been exploring for a very long time. I don’t explicitly talk about it because it’s so technical that, you know, unless you’re the one making the work it doesn’t really matter to anybody else. I like those moments where you can’t actually tell if something is disappearing, and it’s one of the things that I do in my classes – lost and found lines, when you look at an object like a transparent glass on the marble table, you see that there are moments in time when the edges disappear. That’s actually how we see things. But the nature of seeing evolved from our understanding of security and safety: the main reason that we can see stuff is so that we can stay safe, right? Safety means that you know where the edges of things are. You don’t want to fall down, you don’t want to bump into things. We assume that we are connecting all the edges, but we actually don’t see them. So it’s a trick of the eye – your mind’s telling you to be careful. Your eyes lie in that sense. It’s a bizarre technicality that your mind and your eye are in conflict.

Kaushik: Within the charcoal tradition, is porcelain a common subject?

Yanyun: Well, in the classical western charcoal tradition, charcoal has never been considered a finished medium. It’s always just a sketch, and it’s always meant to be thrown. Charcoal has always been considered a medium to get you into painting, but never as a finish point. In the academic tradition, no one finishes a charcoal drawing because it’s not necessary. There’s something about the tactility of the medium and the precision of it which is often not what you associate with charcoal, because charcoal is considered rough. It’s just ash, deoxygenated ash. But if you can push the precision of that to the point that you finish the work, it’s counterintuitive to the nature of the medium. I still haven’t reached a point where I want to work with colour as a medium. I mean, I do have works in colour, or lit to a certain colour, but they’re always as light and not as work.

Jean: We were just talking about charcoal before you came because Kathy was sharing about taking your class. The thing that I love about your work is understanding the technicality and how complex it is to grasp charcoal, and the eraser in respect to that tool in particular and how that technicality is highlighted in still-life. Because it’s always that tension, and exactly what we were saying about seeing, with your eye and your mind, and knowing what it means to render a specific porcelain vase in relation to the other bits and pieces of the entire arrangement. I think there’s so much magic in it because it comes from a place of a classical grasp, but we are moving into a contemporary take on the female, and what it means to talk about these ideals. Even when we were talking about ekphrastic writing, and reading off literary pieces, or responding to literary pieces, and pulling parallels between bodies of works, I think it’s such a complex piece of work to have in relation to the other questions that we will move into later on.

Kaushik: You have this super cool complication to the idea of ekphrastic writing, not exactly ekphrastic writing but ekphrastic painting and drawing, which is that we arrived at another work of art, in this case literature, through the process of creation. It’s not we see – we read the work then we draw, or we see the painting and we write, but it just so happens that your impulse or profession is to draw, and life is giving you literature. Life is giving you painting, life is giving you references. And that’s the next level of ekphrastic writing, that it depends on suspending these different elements. We’re actually saying like this exists all the time, the influence presents itself to you, and your work evolves from that, and I love that.

Yanyun: I kind of think that’s what we actually do. Like naturally, without paying much attention to it. I mean, we get influenced by things we do not plan for, and then your life suddenly takes a different course and you have no idea what’s going on but you’re just riding it as it goes. I think it’s more natural. And I guess, if you link back to my training, it’s always quite an interesting tension, because classical training is very fixed: it’s a way of doing things and you really go through the process of getting precision and polish. You know that there’s no other way to get there, but at the same time it’s the extreme limitations, in contrast with the extreme expansion that’s contemporary art. Because contemporary art is pretty much free association. Trying to find a space where my work can exist, that’s a constant question. Because you know, same work, you bring it to a certain kind of gallery they’ll be like, “This is too classical.” Bring it to another kind of gallery and they will say, “It’s too contemporary.” Bring it to another gallery, they’ll say, “Is this Asian or not?” It’s pulling too many threads and too many tensions at the same time that it doesn’t sit well in any particular mode or category. And I think that that’s how I like my works to be. I don’t see it as an isolated category… I mean it’s still a drawing. Fundamentally, it’s still an object that’s hung on a wall, right? But there’s more to it, I think. And life is way more complex than we give it credit for.

Kathy: Actually I want to go back to a different point – as you were speaking about charcoal, I was thinking about how using charcoal, it’s such a fragile medium because once you breathe too heavily onto it… it’s gone. Your work is also kind of between that stage of almost disappearing and still being there. I think another thing that got my attention was also your use of white space. You’ve talked about this before in your classes: the use of active and passive white spaces. The white spaces in this work are difficult to ignore, and as you said just now, it has a very suspenseful presence. You’ve also had other works that made use of compositional elements in Chinese painting, and I’m wondering if any of that came into this work as well.

Yanyun: I think I would then have to tell you one of the early works that I did in 2013 called Lady of the Seine. It’s a drawing, not very big, of a death mask of a woman. It was a death mask that is very common in academies. I was just drawing that as a school assignment, and then I thought, who is this person I’m drawing? So I did this long Google search and found out that this woman really existed. She drowned in the River Seine in France. She was just fished out from the water, and people were just mesmerized by how peaceful her face was, that they decided to make a death mask of her face. But this face was so sensational that it sort of created a fashion movement: there was a period of time in France’s history where that hair was a thing, and Princess Leia’s hair was supposedly based off that fashion trend. So when I knew this story I thought, okay, maybe I should make her look like she is submerged. She’s in and out of this surface of black, suspended. And the moment that idea hit, suddenly all my lines changed. Previously it was just a study of observation, just trying to get the drawing as precise as possible became, “I want to try and make her look like she’s floating out of black.” And so that, I think, switched my mind. The way I used space changed, and then, you know, when you are forcing yourself to see things a certain way, to create a thing in a certain way, then you realise that everything around it becomes very significant. Like every little blank space, every line, every value, everything becomes significant because you’re trying to create an effect. And that’s kind of very linked to the Chinese classical painting with white, because once you put a mark down you cannot go back. So you plan, or you train yourself to be so familiar with the use of the medium that you know how to create any kind of edge with just one go. So the use of white and charcoal, and black-and-white, they’re not that different. It doesn’t seem as far apart as it looks, like when you look at classical Chinese painting and look at a Renaissance painting they look like worlds apart. They feel like worlds apart. But when you look at the technique, it’s not. It’s weirdly similar, like, there are certain moments where you go, “Oh! So that’s what they were trying to do.” And one of the things that I was trained in when I was at the academy with charcoal and painting, is that you can’t learn how to paint unless you learn how to draw, and you can’t learn how to draw unless you learn how to paint. Because the limitations of one medium is superseded by limitations of the other medium. You have to learn both in order to see both, otherwise you cannot see. So when it comes to traditions for me as well, I needed to be familiar with both. In order to learn each other, it’s always like that. So I guess my understanding of liu bai, which is the Chinese classical approach of leaving white came from studying western academic drawings. And my understanding of how brushworks, and shapes and sections and this approach in Western drawing came from classical Chinese painting. It’s just my way of learning things, that it sort of flipped.

Jean: I particularly love Wu Guanzhong’s transition from ink into ink and abstraction, or ink and white space, like rendering traditional buildings and scenes with so much negative space. And what you just spoke about made me think, that’s precisely where a lot of the magic happens. And he’s such a seminal figure in that time and transition as well.

Yanyun: I love how obvious this is in his work. It’s very useful in class, because then you can, “Nah, you see right!” It’s so easy to use as a visual, and also as a way of learning what the two classical traditions are trying to do. I think the cliche here is “East meets West” but it’s actually not. It’s “technical tradition meets technical tradition”. It’s just different traditions, different philosophies meeting each other.

Jean: When we encountered Hills Like White Elephants, even though it was on a screen, there is an immediate feeling that hits you at your stomach. Because of the white space, it gives depth and distance, that you can imagine the vases, the pieces falling.

Yanyun: Yeah. The work is not balanced. And I guess it does, it will annoy anyone with classical sensibilities. It’s like, “off”. You know the term “pregnant silence” right? That’s how it feels like. It’s not silence. It’s a lot going on, it’s an active kind of white. Pregnant silences.

Kathy: It’s interesting how drawing, or art is able to visualise this kind of like, abstract idea of emotion, pregnant silence, which otherwise we might only feel but not be able to describe in any other way. I think now, the next thing I want to ask is, looking through the works on your website, I got the sense that Hills Like White Elephants is almost this turning point between this other period where you were investigating sixteenth-century still-life traditions, and this later period where your projects started taking on an autobiographical, or autofictional lens? And this is where female identity and the physicality of the female body also become very prominent. I’d love to hear more about that.

Yanyun: Ok, so, Hills Like White Elephants was 2018. And that was the same year I did The scars that write us, which was at the Singapore Art Museum, but it was much earlier on. And I think I showed Hills Like White Elephants sometime in August, and the SAM show was in October, there was that period of time. And I didn’t expect to be asked, I was really surprised when they invited me to do the President’s Young Talent show, I didn’t expect to be selected. I started to massively panic because okay, now I agreed to do a show, in a space fifteen metres long, and I don’t know how to do it. So in the midst of my panic I was going to see other shows, and I bumped into Ang Song Nian, the photographer and installation artist, and Song Nian congratulated me. I told him “I’m stressed out of my mind, I don’t know what to do. The space is so big!” He gave me really good advice: if it’s very big, then go as small as you can. So I sat there thinking, I see what he’s trying to tell me. And so I asked, how small can I go? I asked myself, what’s smaller than a scar? In terms of the works I was interested in doing, let’s go with the smallest but let me not go with the smallest work but the smallest topic. And so the keloid scar, I grew up with it so it has always been there. So I thought let me use that as a starting point, and see how far I can push this. That was how I started to trace a story. I got this keloid scar, I also know my family members have it, so I was like ok lah let me go chit-chat with them about what it was like. What is it like, actually growing up with this? It started to show that actually their experiences and my experiences are not very different. Which is – it hurts like hell, people ask you a lot of questions about it, and when you’re younger people just go ahead and like, “Eh what is this ah?” It’s a very personal experience. And even though it’s so common and so shared, no one actually talks about it in an honest sort of way. It also hurts my feelings when strangers go up to you and poke at your scar. It’s these tiny moments that became the significant part of the story. So I arrived at the shared experiences of scars and all the little tiny details that: if you’re a scar carrier of this type, or actually if you’re a scar carrier in general, with psychological or physical scars, you go through these thought processes. The same kind of annoyances, pressures, and just those tiny moments.

The autobiographical move was very much by accident. The reception of the work was also by accident, because at the end of the day I was very happy with what I had done. But there was this feeling like, I don’t know if anyone is going to care about scars. Fundamentally, who cares about somebody else’s scars? Though I guess there was a certain moment of confrontation when you walk into someone’s personal story, so close and so, you know it’s a fixed experience, that it connects with your own experience.

And so it’s this connection, that is like Hills Like White Elephants where dots start to connect, and then this experience, this kind of like things that link up to the next thing that link up to the next thing. So that was how that move happened. I had all these strangers coming up to me to flash me their scars. The institution was also worried that people would touch the works. They were worried that people would get upset about the fact that there’s boobs and there’s like, you know, pregnancy scars, and all these kinds of things in their face, and my final room is a bunch of text, like words on a wall. So these were like three taboos. You never go to a show and see a wall of text. No one reads the text. You know, and if you put an object there without a barrier people will want to touch it. If there’s nudity, someone is going to complain. And none of the three happened. I learnt that if you present the work well, and there’s a certain kind of sacredness to the way you present, people tend to be very respectful.

So it was fascinating, and a very very important learning journey for me, when a visual object changes from an object on a wall to an experience. Without changing the form, because they are still hung objects. I didn’t have any physical sculptural things. The experience changed. If you present images at a particular distance and it either becomes a very fast sequence or a very slow sequence, depending on pace of viewing. If you walk in a room looking at works at a certain pace, that’s the timing of the story. So if you space the works far, and you light it so it’s obvious that this is the way you’re supposed to go, you pace the viewers’ feelings out. So it was a test, and it worked.

Of course there was the whole social debate about whether you can speak for someone else. Right now the conversations about prejudice, discrimination, race, privilege, it’s all, to me, a fundamental question: can you actually speak for someone else? And the notion of authority as well. There was that moment where I had to contend with the fact that I was a woman, a Chinese woman in Singapore you know, of a certain tradition with a certain background and a certain kind of privilege with a certain kind of flaw… these things became very obvious. But it also meant that it became my arsenal. I came with this toolbox, whether I like it or not. I gotta use it. And so the show, Stories of a woman and her dowry, came from that reckoning. It was a reckoning that, yeah I have a bad relationship with my grandma. It’s really, that’s it. But also understanding that her generation and my generation are fundamentally extremely different. And as much as I don’t agree with it, it is also a revelation of the times. So it is that tension between the positions of the woman in two generations. My tensions and disagreements with my grandma on a personal level, and the anger that I have comes from her source, and so they clicked. So this is the sentiment that I have now, I would say, that when I became aware of, how do I carry someone else’s story?

Kaushik: It seems though, that, to the question, “can you speak for someone else,” you actually did, get close to an answer with the show itself, at the point of creation, you felt like all the works were deeply autobiographical, you weren’t even sure if the subject of scars would be relevant. But suddenly, you realised, through the process of exhibiting, that the autobiographical is actually universal.

Yanyun: There are moments, yes.

Kathy: One last question – you’ve explained before how the etymology of ‘yan’ describes the patterned surfaces of cliff facades. When I was approaching this work, I thought it was fascinating how the Mandarin title 悬念(xuan nian) – with xuan referring to a cliff, and nian referring to thoughts, it also brought to my mind an association with yearning, or desire, because nian the way I use it most commonly as xiang nian, which is thinking of something, like oh I want this, I’m thinking of this. For me, these associations added another layer of emotion to the drawings. Listening to you talk about all this, and from reading that short piece on your website, names, words and language, they all seem so central to an understanding of this series, because they are what give meaning to it. Could you share more about the role of language in your practice?

Yanyun: I went to a school called the European Graduate School, in Switzerland, for my Masters and PhD. One of the fundamental things that I appreciate from my many years there was their sensitivity to words. I learnt the significance of forming a question, and what a good question is. Because every word you choose has a different etymology, which is the historical baggage that comes with each word being used. The word etymology means one thing, but the gesture of etymologizing means a completely different thing. It’s conflicted. The word itself is conflicted, the whole study is conflicted. They are trying to do different things: one is searching for the essence of a word, and one is searching for the origin of the word. It doesn’t work. And there’s a beauty and an irony in that. And knowing that, breaking apart the word etymology and understanding what’s being done, how it’s done, that realization has forever stuck with me. That the meaning of things and how they are used can be so significantly different that it opens up endless possibilities of trying to understand a word. It’s never static, and etymology does not have a linear storyline. This word was being used, then this word was being used again, then suddenly in a different time it means something else. Someone else hijacks the word, or colonizes the word, turns it into some other being altogether. It’s a very disjointed history. Knowing that meaning is non-linear was very significant. Meaning is highly dysfunctional, and so if you embrace it, you can create any kind of thread between things. So long as it logically makes sense on some level, on some level if it clicks, it will click, and click very well. My experience as a postgrad was all about trying to understand what it means to ask a question and what a question is. Language becomes very significant because I’ve become way more sensitive and way more careful, and way more articulate. I was very not as articulate before my postgrad, because I saw the world visually. I work visually, I never had to use words. And that was one of the flaws that I had. I needed to skill-up and try to understand what the hell I was trying to do and say. So that changed my own journey, this was even before I practiced art the way I do now. For me storytelling began from drawing and animation, that became training, became language, and then came back to storytelling. Right now I’m at this stage where story is very significant and there’s only that many autobiographical stories you can tell! And I think what I’m reckoning with is what kind of stories do I want to tell now, that is not about me, that moves out of the autobiographical for the moment to let experience happen, then I collect more things that I can actually talk about. That’s all language.

In 2015, Lim’s works were presented alongside those of six other photographers in Rediscovering Forgotten Thai Masters of Photography, an exhibition led by Thai artist-curator Manit Sriwanichpoom. An instinctive reaction to this project title might be to ask: What made these photographers’ works distinctively Thai, and what made them especially masterful?

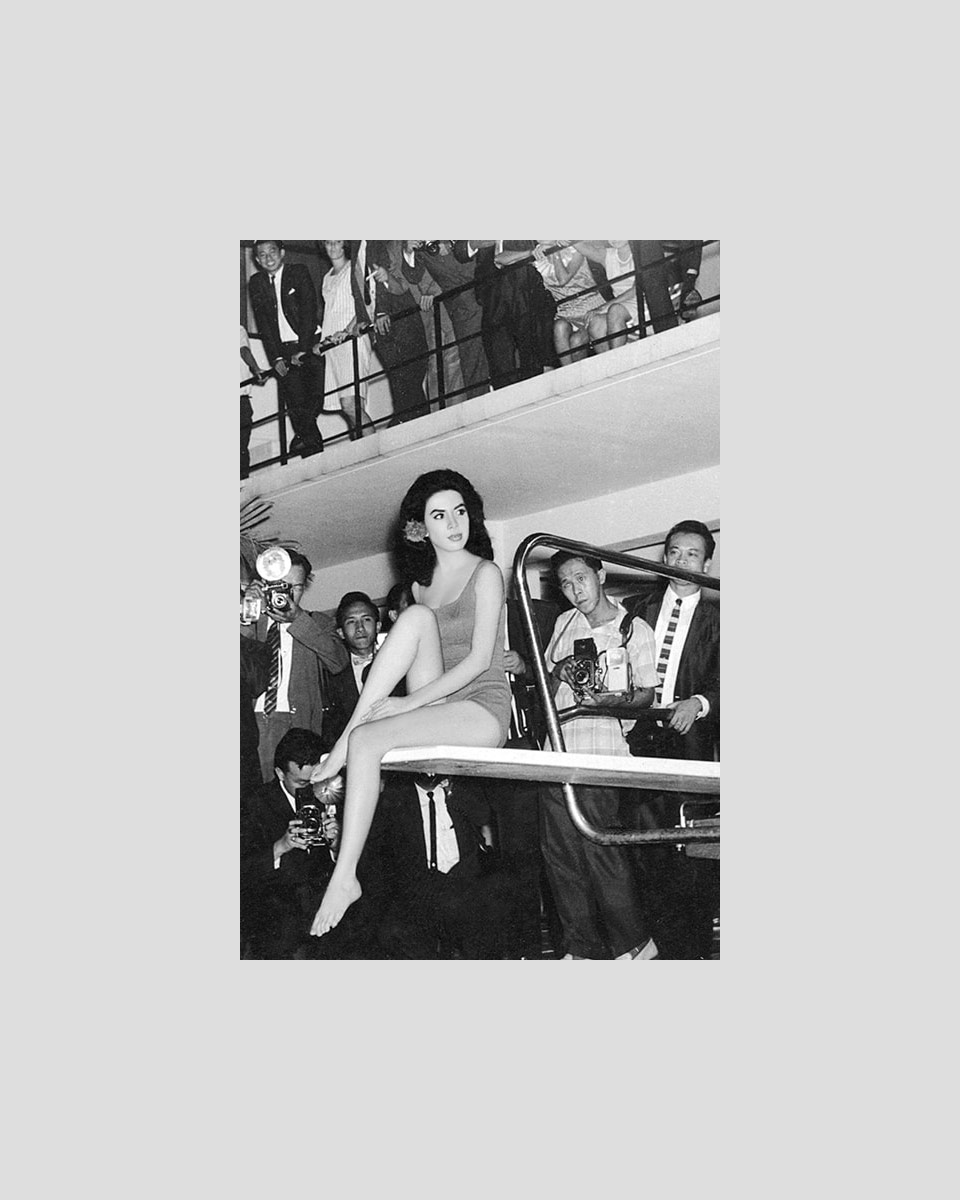

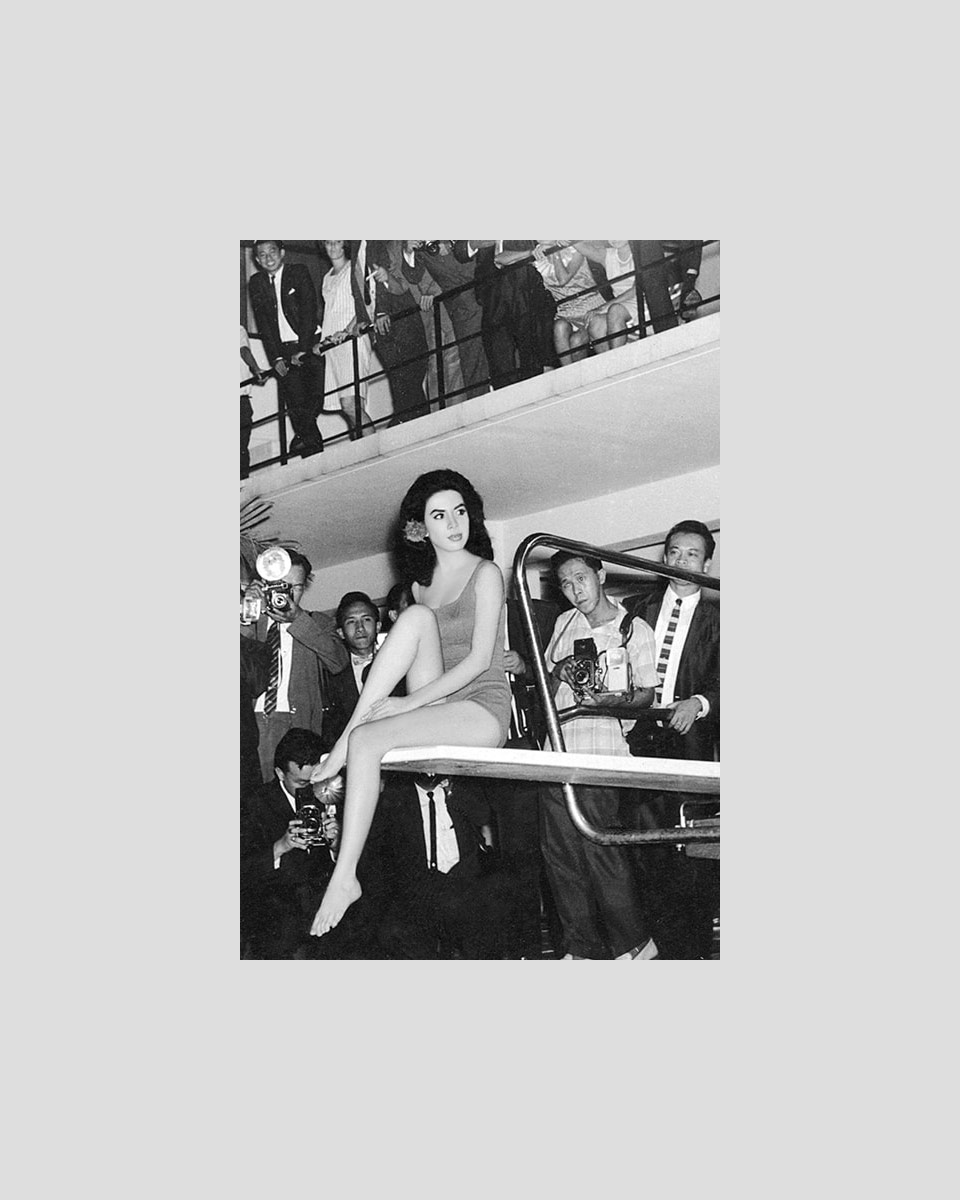

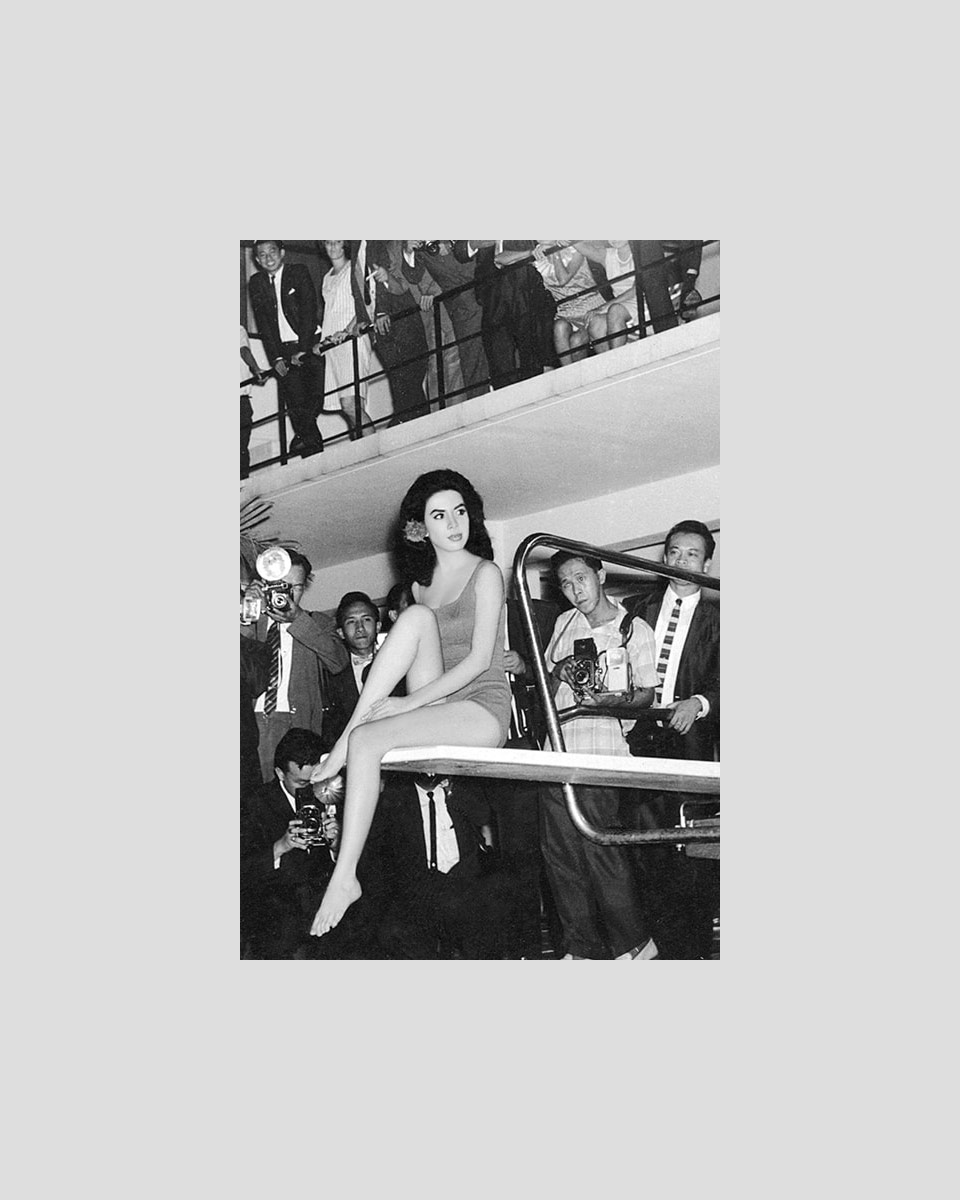

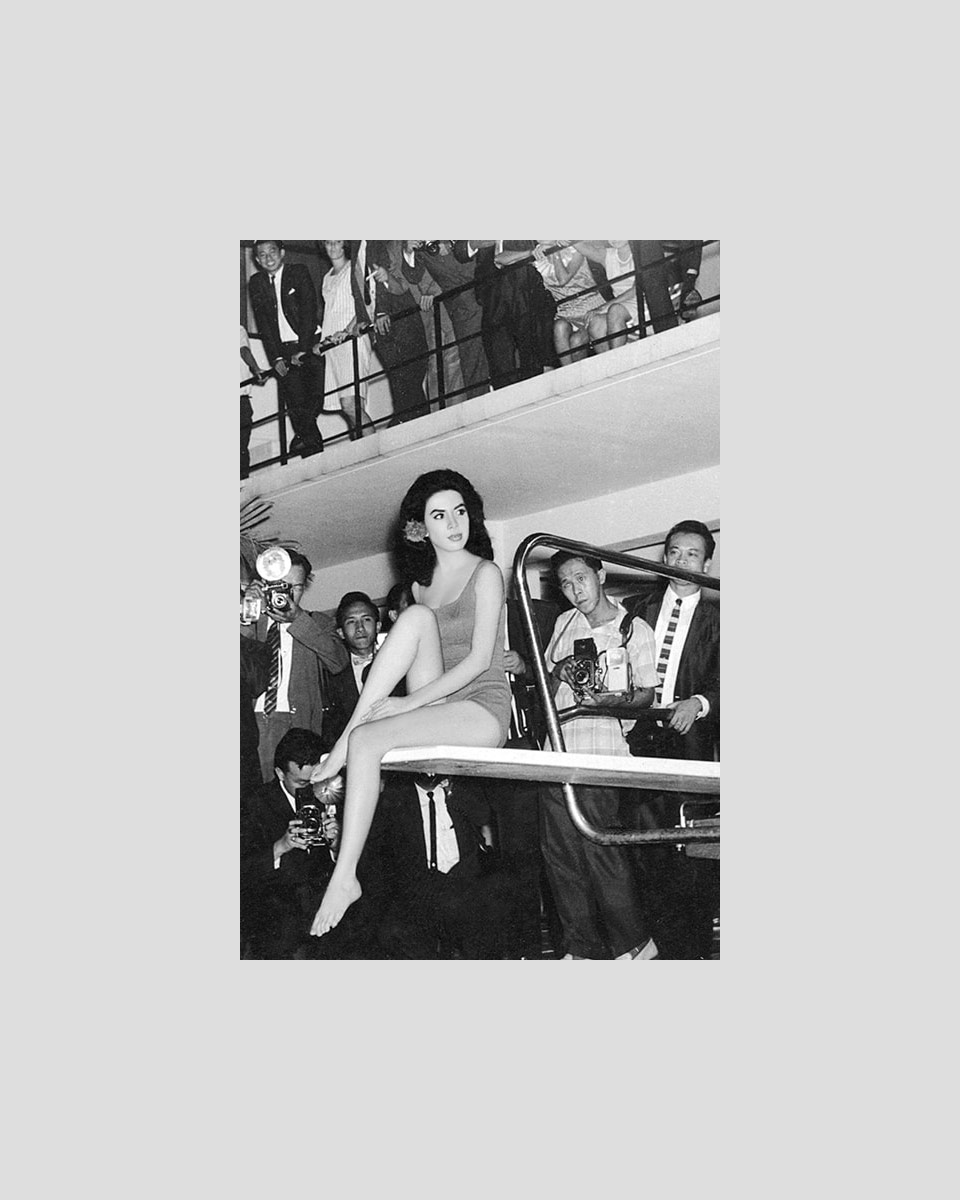

Lim’s images resemble the aesthetics of 1960s Hollywood far more than Thai iconography of the same era. His 1967 femme fatale portrait of Phusadee Anukkha-montri, for instance, features a Mauser C96 pistol, popularised in the James Bond film From Russia With Love (1963).

While femme fatale archetypes are often pejorative in American cinema, the women in Lim’s photographs are proudly celebrated. And for good reason. The 1960s was a golden age for Thai cinema, and in 1965 Apasra Hongsakula became the first Southeast Asian winner of Miss Universe. Actresses and models were not only the faces of beauty pageants and local billboards, they also became representations of a modern Thailand on the world stage.

How do individual and collective identities collide, and how does visual culture mediate this relationship? Archive and mirror alike, Lim’s photographs open up new ways for us to understand our own time.

After graduating from the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Puipia launched his own label SHONE PUIPIA in 2017. He works from his central Bangkok studio and multidisciplinary space, soi sa:m.

The son of two established Thai artists— Pinaree Sanpitak and Chatchai Puipia— Shone grew up drawing cartoons and imagining fantasy worlds. Today, his collections draw inspiration from the likes of Grete Stern’s surrealist photomontages, Sarah Sze’s installations, and David Hockney’s graphic compositions.

In Conversation with Shone Puipia

Kathryn:

Thank you, Shone, for taking the time to talk with us. It’s been a pleasure to dive into your work the past few weeks. We have a few works from both your Wild Bunch and Brighter World collection for Appetite’s inaugural show, She/Her. That show features artists that explore and work with the female form. What is so unique about your work is that your designs tell stories and your collections have really strong narrative qualities. How exactly do you go about telling a narrative through textile? Are there certain looks in the collection that you see as points in the narrative arc?

Shone:

For the Wild Bunch collection, it is really about the narrative. From the first to the twelfth look, the textile, the material, and the techniques really tell the story. I really wanted to start with references to actual Victorian garments – pieces in white fabric. The collection is an alternate story to the movie, Picnic at Hanging Rock, so I wanted to investigate her travel through the woods– what could happen there. So the pieces have this raw quality. Raw and frayed edges. The collection starts off white and pure, then I inject colors and more wild elements like the fur I made by felting yarn and feathers together. In the beginning, there is the second look where the fur is just on the back of the white dress — hidden red and oranges. By the end, it’s really an explosion of materials and colors.

Kathryn:

I had read about your warp painting technique and was wondering if the fabric for that look’s blouse was made using that technique?

Shone:

For that kimono, I worked with Jim Thompson, the company that makes Thai silk. I was really interested in this technique where they print the pattern onto the yarn before it’s woven into the fabric. You get this blurred out effect from the shifting of the yarns. Their examples were more abstract motifs, but I wanted to see what it would look like using photographic artworks. So, I made a garden collage with flowers, plants, mixed with shells. That was the source of the fabric.

Kathryn:

In that collection you explore the dichotomy between the innocent Victorian girl and this wild, sexually liberated woman. What are your current and past conceptions of femininity? How has your understanding of womanhood changed over time?

Shone:

When I was in school, I created characters based on icons, figures in movies, or people I was inspired by. I would make this “ideal” woman for the collection. Increasingly now, since the collections are not purely womenswear anymore, it has become something very personal–what I want to wear, what I’m feeling at the moment, what the people around me want–my mom, my clients, people I meet at the show.

Jean:

I am very curious as to how you choose these icons. What stands out to you in these women?

Shone:

I like strong female characters. These girls from Picnic at Hanging Rock– they are wild, they broke away from formality and went on this adventure. A collection I did in my second year of school was based on the Royal Tenenbaums; I was drawn to Margot Tenenbaum. She is very feisty, and that’s what I really liked in her character. They have… somewhat masculine qualities to them–they aren’t traditionally feminine. That’s what I try to evoke in my work as well.

Kaushik:

While we’re on the subject of both Peter Weir and Wes Anderson, could you tell us a little bit more about your love for film? How long has it been a part of your life, and when did you realize it would be core to your practice?

Shone:

We’ve always been a movie-watching family, even pre-COVID. We would always go to the cinema every week to catch all the movies. You can get a lot out of a movie–storytelling, moving narratives, a certain aesthetic quality. Films take you somewhere else, and I feel like that can also be applied to fashion.

Kathryn:

Soundtrack is also another element to films. I noticed for the Wild Bunch show, you chose a Creedence Clearwater song, which I loved.

Shone:

Yeah, for that show, I really wanted to create a fun moment. It was the ending collection for that night.

Kathryn:

Could you discuss the increasing role that androgyny plays in your practice?

Shone:

I started out in womenswear, but I felt like I was missing out on all these fun clothes. I like to dress up, and I often cannot find what I want to wear in the market. So, it was really a decision to put myself into the collections–really making clothes that I would want to wear. Now, I don’t see clothes as having gender. If you want to wear this or that, it doesn’t really matter. If it looks good and you like it, it’s something you should go for. That’s what I have wanted my recent collections to be about.

Kathryn:

Your mother’s work is also featured in the show, and I was hoping you could speak about your working relationship with her. She’s joked before that part of her job is to be your assistant. How do you work together, and how do you influence each other?

Shone:

We always see what the other person is working on. It’s nice to have the opinion of a woman when you’re designing things for women. She doesn’t have a model-type body, so it helps to think of ways to design clothes for different body types. In terms of design, we give and take from each other in form and material. One of the main materials used in the collection–mawata silk (raw silk fibers)–I discovered through her installation work (called “The Room”). I was also there to help her with the installation. I wanted to use it in garments, but it’s quite a fragile material. I ended up encasing it in silk organza, so you still get the texture of the raw silk while still being a functional garment.

Now, for this new collection, other than the clothes, I asked mom and dad to make artworks interpreting the collection. Mom made calicot patterns for the collection. Dad made an installation. Grandma did cross stitching embroideries for the shoes in the collection.

Kaushik:

You’ve told us how your mother has influenced you. Could you tell us how you’ve influenced your mother?

Shone:

She started working with the breast motif after I was born. So motherhood was my influence! She started doing these “Bare Silhouette” works where she would place garments on the canvas; she got more involved in that type of work when I started working in fashion.

Shone:

There’s also that series she made of breast-stupa hats, and I was the model for that when I was really young.

Kathryn:

Your collages for the Wild Bunch collection really demonstrate your personal interest in celebrity culture and this type of fashion photography.

Shone:

I like these photographs from the past. I’m very attracted to this sense of nostalgia…this lost glamour. I don’t see those sort of characters nowadays. That’s why I go back to these kinds of photos.

Kathryn:

What is it like to have been born and raised in Southeast Asia, then going on to study in Antwerp and receive that globalized influence, and ultimately return to Bangkok to continue your design work? Do you incorporate those global influences into your fashion design, and if so, how?

Shone:

What I do now is very much informed by studying and living in Europe. Since I started doing the brand here in Bangkok and hearing feedback from people, they all feel that I’ve introduced something really different to the Thai fashion scene. I think I work very differently because of my experiences and the people I hung out with. My Antwerp years really inform a lot of what I do.

Jean:

Between Europe and Thailand, do you see any differences in the perception or ideals of what it means to be a woman? What does it mean to dress women of different geographies?

Shone:

When I was in Europe, we were all with other fashion students and they were all really fearless dressers. Coming back here, it’s much more toned-down. In the young generation in Thailand, I see more individualistic dressers. The culture has changed.

Jean:

Within this youthful, more daring group in Thailand, would you say ideas of femininity are also changing?

Shone:

Regarding gender, I think we see much more fluidity now. Everywhere but also here.

Kaushik:

I’m wondering if you think of your practice as political. How important is it to think about contemporary politics when designing your collections?

Shone:

I don’t think of myself as a political person or someone who is trying to make a statement. I do this to present a vision–a vision of what the world could look like, what people could look like if we disregard differences like race and gender. I don’t actively try to make a stand.

Kaushik:

We are very attracted to that idea you just described: to look past race, gender, and all of these other arbitrary differences. That’s exactly what we’ve tried to do as a restaurant for the past 3 years now.Have you thought about where this desire comes from? Why are you interested in this idea of an ideal world?

Shone:

For me fashion is about creating pure beauty–I’m trying to put this out in the world because I don’t see it around me. I think that’s my personal impulse to do this.

Kaushik:

Do you have a specific moment when you knew you wanted to be a designer?

Shone:

I fell in love with it through the craftsmanship of it. It was during my high school years when I was figuring out what I wanted to study. I was taking these French classes and these pattern-making classes. Once I started to take those, I really loved the craft and the skill side of fashion. Just like with my parents, to do this kind of work you need the skills, not just the ideas. So it’s very important for my collections that the making, the patterns, the finishing, and the construction of clothes are well thought out and well executed.

We’re still a small studio, so I work on the patterns myself. To be able to oversee every step of the process is very important to me. I am very hands-on. I guess I think of myself more as a coutourian, not like these big houses where the designer doesn’t even design anymore. I still really like this tactile part of the work, to be hands-on with the pieces.

Kathryn:

Has your dedication to craft and tactile engagement with your works been the main reason you’ve resisted venturing into the ready-to-wear genre?

Shone:

Yeah, I don’t want to become big and then have to compromise. I would very much prefer that we work as a small team, making everything in house so that I can ensure the quality for my clients. It’s a practice I want to promote nowadays because I feel that it’s getting lost, especially in the wake of fast-fashion brands. I want to bring back this sense of craftsmanship and quality to clothes–something that will last a long time.

Kaushik:

We’ve just lived through a very strange three months. What’s on your mind about collections that are to come?

Shone:

It’s difficult now… I don’t have the perfect solution to it, but the dilemma we have now as a studio is what to create when people are not buying for quality anymore and instead turning to fast-fashion. When People are not going out and there are no events, it’s difficult to continue making these extravagant clothes.

So for the collection we just launched, it was suitable to the times. We decided to go with more solid colors–less of a focus on prints and extravagant details. It was more about separate pieces and showing the garment side of our work. At the end of the day, I would much prefer to go back to presenting something fun. We need that in the world.